Photographs by Dick Kinler

When Rocco “Rocky” Tassione was growing up in Hurst, Texas, he had a knack for mending sickly ferns and ponytail palms. “As a kid, I’d save all the neighborhood plants,” the specialty farmer says. But nearly 30 years would pass before Rocky was “hit over the head” with the epiphany that led him to put that childhood passion to work. Not a year into his marriage, the dry-cleaning manager said to his wife, “Let’s grow stuff out in the country.” That was 1991, and the seed for Tassione Farms was planted. The farm sits on 150 acres of rolling farmland at the northernmost tip of the Hill Country near Stephenville in a geological warp called Cross Timbers.

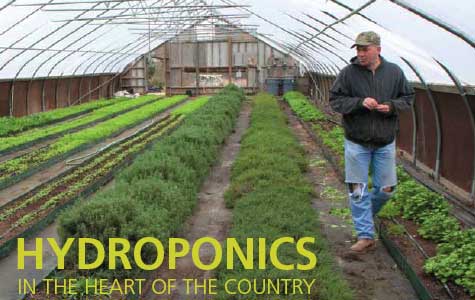

The heart of the farm, where the Tassiones live, is a 3.5-acre parcel with eleven greenhouses jutting up from the horizon along a winding, caliche road just beyond “downtown” Patillo. After leaving “downtown”, which consists of a feed store and an outdoor tabernacle, I make a few wrong turns before arriving at the farm to find Rocky motioning me through the gate. He’s dressed for success, country-style: torn blue jeans, gray sweatshirt daubed with paint and dirt, and camouflage gimme cap.

This farm may not look like much, but if you’re in a restaurant during winter or early spring and taste a tomato as vibrant as summer’s best, it’s probably the Tassiones’. From their greenhouses, Rocky and wife Celeste coax year-round supplies of baby lettuces, exotic microgreens, tomatoes, herbs, watercress, edible flowers and more.

Twice a week Rocky delivers fresh-cut orders to Dallas and Fort Worth restaurants, most more than 100 miles away. The restaurants, which Rocky names by mentally tracing his delivery route, include Bolsa, Tillman’s Roadhouse, Stephan Pyles, Parigi, Urbano Café, York Street, Ava (not driving to Rockwall but meeting the chef at a designated location), Nick & Sam’s, Rathbun’s Blue Plate Special, Shinsei, Bailey’s Prime Plus (North Dallas), Central 214, Suze, Cadillac Ranch in Irving, the Gaylord Texan in Grapevine, J.R.’s in Colleyville and Grace in Fort Worth. He recently added Preston’s in addition to the Rosewood Mansion.

Most of the greenhouses have shallow, raised hydroponic beds built atop T-posts that you would normally use to string barbed wire. “We drove a lot of T-posts,” says Rocky, “about 4,000 T-posts over the years.” Each greenhouse measures approximately 30-by-96 feet and has an 11,000-gallon tank through which water with natural fertilizers is circulated. “We recycle the water, so there’s no runoff,” Rocky says. “Once a month we change the water and pump it out into fields that have winter wheat. “Deer eat it all winter long, and then the quail and doves and turkeys come in.”

Since he moved to the farm in 1997, Rocky says the contents of the beds have shifted with tastes. This year, less space is devoted to watercress as restaurants clamor for more baby lettuces, baby vegetables (new this spring), pea tendrils and other items. Rocky’s microgreens include arugula, Red Russian kale, Giant Red mustard, Osaka mustard, purple kohlrabi, Triton radish (with its hint of orange) and “beautiful purple” Italian plum radishes. Some add color; some, flavor. When it’s time for a salad at the Tassione home, Rocky and Celeste can reach down under the beds, where fallen seeds have become full-grown plants.

But the Tassiones defy logic in growing these luscious winter tomatoes. They take up most of one greenhouse, their green stems as big around as a thumb, snaking back and forth among the stakes. “By the time we pull them out in July, some are 60 feet long,” Rocky says. Just like grapevines, they’re trimmed and trained to grow for optimum production-—not just quantity, but quality. “The Sun Golds,” he says of the cherry-size, orange orbs, “now those things have a following. They taste like candy-—very sweet with a mild citrus flavor, with acid bite. Delicious.”

Most hydroponically grown tomatoes pale next to field grown, and it’s startling to discover Rocky’s. His secret? “All the minerals in the ground are in our water,” he says, and the minerals are what boost the flavor. Unlike most farmers, Rocky grows tomatoes full-bore from August to July, pulls his plants, and then replants for the next year.

While most of the greenhouses are set up for hydroponics, Rocky also maintains a couple of houses with dirt beds. In those he grows woody herbs, such as oregano, thyme and rosemary, or baby vegetables. The latter includes real baby carrots, he emphasizes, not the cut-down nubs you buy at the store.

The deer and birds that forage on the field wheat where he releases the greenhouse water are part of the reason the Tassiones wound up on this land. “It has been in my family since the ‘60s,” Rocky says. While he and his brother were growing up, their father brought them here to hunt.

“I pretty much knew from the beginning that Rocky wanted to live on the ranch,” says Celeste, a city girl who was an executive assistant when they met. “I think our second or third date was a trip to the ranch.” Accommodations consisted of a ‘50s-era trailer. “He didn’t tell me there was no heat, water or potty. I still get ribbed for showing up with a hair dryer. He hiked me all over the property, then had me shoot targets. I think it was all a big test. I must have passed because from that point on, we had a 10-year goal to start some kind of business and live on the ranch.”

They were married July 4, 1991, and set up housekeeping in Richardson. “We were foodies and winies,” Rocky says. “We’d go out on the weekend, eat good food, drink good wine and people-watch.” Then the epiphany struck: He could grow specialty crops on the family land while enhancing the environment for wildlife. He started studying hydroponic gardening, got a plumber friend to help with a design, and in the summer of ’92 built his first “greenhouse” in the couple’s two-car garage. You know: grow lights, Mylar-lined walls, hydroponics system and a carbon dioxide generator. Everything you need to grow killer marijuana.

“The police came out twice,” says Rocky, laughing. For four years, the Tassiones farmed in their garage, selling some of their harvest and squirreling away money for the transition to the ranch. “I moved out here first,” says Rocky. Celeste followed six months later. Eventually, they would build a modest home, whose windows look out on a clearing of oak trees. They have daughter, called Scout after the To Kill A Mockingbird character, and a son, whom they named Stone.

Scout’s birth in June 2002 was particularly memorable. While Celeste basked in the glow of motherhood, she thrilled to a lightning storm in the distance outside her hospital window, unaware that it was over the ranch. “The boughs of the 30-foot post oaks were touching the ground,” Rocky says. When it was over, four Tassione greenhouses had been wrenched from the ground and one had been smashed.

“They were destroyed,” Rocky says. With no insurance, it took them a year to save enough money to rebuild.

Probably their worst moment, though, was when Celeste was bitten after stepping barefoot on a copperhead. “It felt as if an iron-hot hammer with a nail sticking out of the end slammed into my arch like a train,” she says. Rocky takes over the story: “We grabbed the kids and called 911 in the car. They alerted the hospital and the state troopers.” Rocky sped to the hospital in Stephenville, where Celeste was treated and stayed overnight. Her foot took four months to heal.

But tenacity and vision have their rewards. The sharp rise in demand for locally grown foods has not only buoyed the Tassiones’ business, it has shifted the way chefs view farmers. “The climate has changed dramatically since we started,” says Rocky. “With the push to buy local, the chefs are much more understanding of the farmers’ plight.” When one of Rocky’s regulars called on a recent Monday night for a Tuesday order, Rocky gently told him no. “We need to get our orders in by 2 p.m.,” he says, “to get everything cut, packed and refrigerated for the next day’s delivery.”

“It’s hot, hard work in the summer and cold, wet work in the winter, seven days a week,” says Celeste, “but I am proud of what we grow.” Not only is she assured of the food’s wholesomeness, she loves her family’s country life, especially what it has meant to the kids. “We get to watch deer and birds every morning,” she says. “I watch Rocky teach Stone and Scout good hunting ethics and feel proud that we are passing on a lesson of wildlife stewardship.” In fact, Celeste has only one reservation: “I just don’t like the snakes anymore.”

KIM PIERCE is a Dallas freelance writer and editor who’s covered farmers markets and the locavore scene for some 30 years, including continuing coverage at The Dallas Morning News. She came by this passion writing about food, health, nutrition and wine. She and her partner nurture a backyard garden (no chickens – yet) and support local producers and those who grow foods sustainably. Back in the day, she co-authored The Phytopia Cookbook and more recently helped a team of writers win a 2014 International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Award for The Oxford Encyclopedia for Food and Drink in America.

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/