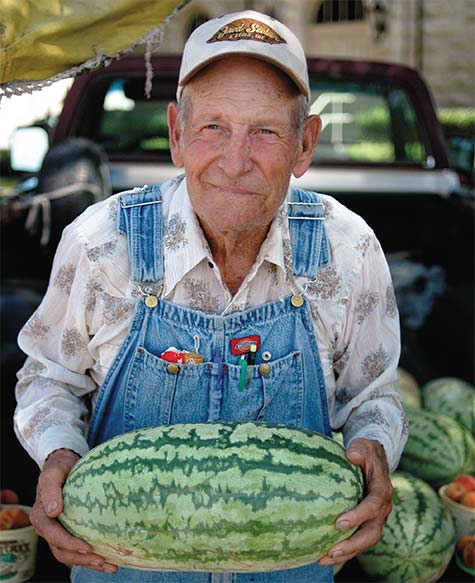

Holding watermelon—Mr. Kenneth Hopson, born and raised in Glen Rose.

Holding watermelon—Mr. Kenneth Hopson, born and raised in Glen Rose.

Though he’s retired after 35 years of selling produce, you’ll still find him

most days sitting at the town square. (Photo by Richard Adams)

Biting into a juicy slice of an ice-cold Texas watermelon is one of summertime’s sweetest pleasures. Nothing symbolizes the leisure season more than a mountain of rotund, green-skinned melons stacked several feet high at a local market.

In my childhood, watermelons were an occasional outdoor treat, associated with picnics, Texas Rangers games and fireworks displays.

Whenever my father had an extra day off, we’d prepare for the three-day weekend by picking one up from an older man who sold them from the back of his truck. He was always easy to find as he parked under a big tree near the Waxahachie post office, sat on the tailgate and sold his harvest cheap. They were always huge, vine-ripe and delicious.

Originally cultivated in Africa, the watermelon has traveled a circuitous route to become a part of our heritage. Popular with the ancient Egyptians more than 5,000 years ago, the seeds found their way to India and China through trade routes. The Moorish conquerors first planted them in Southern Spain, and European colonists and African slaves introduced them to the New World. Spanish settlers were harvesting watermelons in Florida by 1576, and the British colonials were doing the same in Massachusetts by 1629.

“Many Native American populations in New Mexico were growing watermelons decades before Spanish arrived in the area,” says Melissa Kruse-Peeples of Native Seeds/SEARCH, a non-profit organization in Arizona that conserves the crops important to the cultures of the Southwest. “They received seeds via trade and exchange from friends and family living in colonized areas. Watermelons are amazing, and it is not a surprise that this new fruit would have traveled so quickly.”

“A ripe fruit will have a slightly more hazy

look to the rind, and one that’s not fully

ripe will look much more shiny.”

Watermelons are a small testament of how diverse cultures come together, united by a common philosophy, to share what they have to offer.

Down through the generations, watermelons have become an important cash crop in Texas. Needing about three months from seed to harvest, they’re planted in mid spring, showing up in farmers markets and roadside stands by June and reaching their peak by July. Picked in fields within an hour or two from the North Texas farmers’ markets, Texas melons can be purchased at the peak of ripeness.

The Lone Star State is a top producer because our summer heat and long growing season are similar to the climate of western and southern Africa where the crop is indigenous, says Ryan Schmitt, a horticulturist with Botanical Interests, an heirloom seed company in Colorado.

“People think of the area around the Sahara and imagine that nothing much grows there, but I’ve never seen as many watermelons stacked as high in my life as when I lived in western Africa,” says Schmitt. “Sure, you need water for watermelons, but just as importantly, you need heat for the sugars to develop. And, that’s why they do so well in Central and North Texas.”

Like tomatoes, they have been bred throughout the centuries into a broad spectrum of varieties. “They’re all over the map,” says Schmitt. “There are ones with pink flesh, yellow flesh, orange flesh and white flesh with red seeds. There are hundreds of varieties.”

A common trait among most modern varieties is their sweetness, but that has not always been so, says Schmitt. Breeders try to satisfy the sweet tooth of the population and have done so with increasing success over the centuries. In contrast, the citron melon, popular among the Victorians, was a flavorful watermelon that could hardly be described as sweet.

Through selective breeding, seedless varieties are the most recent development in the history of the crop. They’re a success story of selective breeding, not genetic engineering.

Seedless hybrids are the product of dedicated horticulturists who have developed techniques to breed a plant that has four sets of genes with a plant that has only two sets. The result is a natural, hybrid offspring that had three sets, known as a triploid, and this offspring is therefore sterile, much like how a mule is the sterile offspring of a horse crossed with a donkey.

“There’s something about having that third set of genes that makes a watermelon seedless,” says Schmitt. Generally regarded as too expensive for the home gardener, seeds for seedless hybrids are in high demand among commercial growers who can justify their investment.

Although we may have easy access to a plentiful commercial crop each year in Texas, Schmitt says that there’s good reason for the home gardener to set aside a little space for the crop. “It’s the difference between a good watermelon and one that makes you step back and say, ‘Wow! That’s just amazing.’ That’s how I’d describe a homegrown watermelon.” In an area as small as a 4-foot square, a home gardener can expect four or five melons from three to four vines. Heavy clay soils in parts of the state are not as hospitable to the crop as loamy areas, but by adding a light, airy compost and plenty of lava sand to our native soil, we can build up a raised bed that’s perfect for melons.

“You want a good, evenly moist soil that’s well drained. Watermelons don’t do well in soggy soil, but they can be grown even in a heavy clay soil as long as it’s well drained,” says Schmitt.

Some of the most popular varieties among home growers are:

Crimson Sweet—The melon that we recognize as a watermelon, with a blocky, round shape and a light and dark green striped rind.

Sugar Baby—Perhaps best described as a black bowling ball, the round, dark-skinned fruit yields a melon that weighs less than most but packs a powerfully sweet red flesh in a small package.

Charleston Gray—A flatter melon with a light green rind and an oblong shape.

“These are standard varieties that you’ll find in most backyard gardens, and they’re a lot like the watermelons you’ll find at the farmers market,” says Schmitt. “Of course, commercial growers are growing very specific hybrids that have been developed for mechanical harvesting and disease resistance, but what they’re growing are doppelgängers of these homegrown varieties.”

Regardless of the variety, the most important factor in picking the best one, in the garden or at the market, is detecting ripeness, and almost everyone is familiar with the acoustic test, comparing the sound made by thumping a finger against the rind of the watermelons. But Schmitt, also a musician with a keen ear, says that’s never worked for him.

“I have a list of things. First, I check the underside of the watermelon, which is the light, sometimes white part of the rind where it was making contact with the ground when it was out in the field. When a melon is ripe, that part will turn to a creamy color, almost the color of a manila file folder. Then, there’s the rind. A ripe fruit will have a slightly more hazy look to the rind, and one that’s not fully ripe will look much more shiny. And finally, there’s the tendril at the part where the melon was joined to the vine. It should be curled up and yellow or brown,” says Schmitt. “As far as the thump test, I’m sure there are some old timers out there who know what a ripe melon sounds like, but it’s never worked for me.”

Picked in fields within an hour or two from

North Texas farmers markets, local watermelons

can be purchased at the peak of ripeness.

MARSHALL HINSLEY is a writer and photographer who lives with his wife on a 40-acre farm south of Dallas. With a passion for growing sweet, vine-ripe specialty melons, he's also a sustainable farmer whose mission is to grow food crops in a way that improves the ecosystem and benefits wildlife as well.

- Marshall HInsleyhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/mhinsley/

- Marshall HInsleyhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/mhinsley/

- Marshall HInsleyhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/mhinsley/

- Marshall HInsleyhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/mhinsley/