Pioneers of Grass-Fed Meat

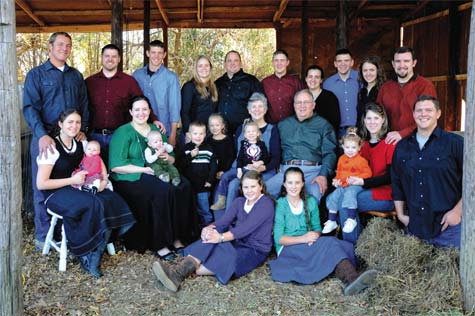

Robert & Nancy Hutchins with Family (Thanksgiving ’10) Front Row: Abigail, Ruth Middle Row: Sarah (holding Caroline), Mary (holding Charlie), Kyle, Natalie, Nancy (holding Alaina), Robert, Jodie (holding Kaitlyn), Mark Back Row: Michael, Eric, Samuel, Analiese, Matthew, Caleb, Elizabeth, Stephen, Katherine, Brian.

Photography by Kelsi Williamson

Rehoboth Ranch, one of North Texas’ pioneering grass-fed meat producers, helped put the “clean” in local meat, poultry and eggs. A fixture at the McKinney and Coppell farmers markets, Rehoboth and its consortium partners at Texas Meats first broke the pastured meat barrier over 10 years ago at the Dallas Farmers Market, where they can still be found in Shed 2. Robert Hutchins, patriarch of the family that owns Rehoboth, notes that Dominion Farms in Denison was introducing the grass-fed concept to Fort Worth at the same time.

“We don’t think there’s any better way to raise animals to make them more nutrient dense, and our meat is optimally nutritious,” says Robert. “You can’t get better genetics, grass, soil and production methods.” This results in what a lot of people like to call “clean” meat, poultry and eggs – naturally and sustainably raised on organically grown pasture without antibiotics, hormones or other chemical additives and, where appropriate, fed only non-GMO, organically grown grains.

Rehoboth’s animals are raised on rolling pasture at the 287-acre spread north of Greenville in East Texas and on 100 neighboring acres. Its ruminants—cows and goats—never consume anything but “grass and mother’s milk.” The only exception, says Robert, was during the winter of 2011-2012, when drought withered the grasses and he supplemented the animals’ diet with hay. The non-ruminants— chickens and pigs—are omnivores, so they also chow down on non-GMO feed (grown without genetically modified organisms). “Grain is a natural part of pigs’ and chickens’ diets,” says Robert, and both also have continuous access to green grass, although he’s had to modify the way he raises chickens because of predators – moving egg mobiles to outlying locations and using predator-proof pens instead of hoop houses.

With their eight children in tow, Robert and Nancy moved into the 1,100-square-foot house that would become the nerve-center of Rehoboth Ranch two weeks before their daughter, Katherine, was born in 1995. They named it Rehoboth, despite its trashed and tumbled-down condition, Robert says, because “we were reading through the [Bible] book of Genesis as a family. We liked the Hebrew word for ‘God’s place’ that was the name of a well dug by Abraham and re-dug by Isaac when he found a place to settle down where he could be at peace with his neighbors and all those in the lands surrounding.” The low-slung, one-story house at the end of a tree-lined country lane has since been expanded to 4,000 square feet, and of that original boisterous crew, only five remain solidly at home: Elizabeth, 27; Katherine, 18; Caleb, 16; and 15-year-old twins Ruthie and Abigail.

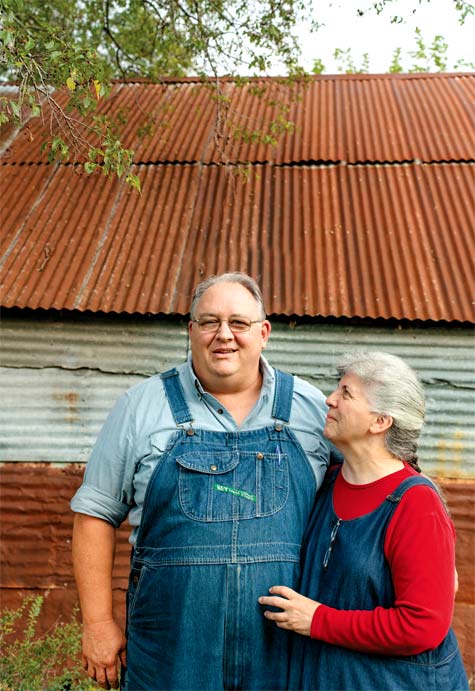

“We try to mimic nature as much as possible,” says Robert, clad in farmers’ overalls and seated in a well-used recliner-lounger in the great room off the kitchen. “Settlers 150 years ago raised cattle on the open range,” he says. “Pigs roamed freely in the river bottoms and foraged their own food.” That changed when the land was plowed up to grow cotton, he says. “We’re getting back to what the climate and soil will support. We believe it’s livestock.”

Sounds idyllic, doesn’t it? But sustaining that beautiful philosophy without going broke requires true grit.

The first lesson of 2000, also the year Robert quit his job as a defense industry executive, was: “You may know how to raise a small number of animals with no problem. But the difficulties of added challenges outweigh the benefits of economies of scale.” According to Robert, going from 200 to 2,000 chickens was complicated. “Another lesson was we don’t have the manpower to breed pigs.” Adds Elizabeth: “Farrowing is an art.” Now they secure weaned piglets from a vetted partner-source and raise them to maturity.

But by far the harshest lesson has been nature’s penchant for defying expectations. Raising grass-fed livestock means you depend on grass. “Ninety percent of customers don’t understand the connection between how much it rains and how much meat we can produce,” says Robert, adding: “It takes two-and-a-half years to raise grass-fed beef.” In 2005-2006, the microclimate where the ranch is located suffered a 100-year drought. But as is typical of a drought weather cycle, rainfall more than doubled the following year. “In 2011, we had the state’s version of a 1,000-year-drought,” says Robert.

“It was the worst in the state’s history.” That was followed by only normal rainfall in 2012, not the cycle-fulfilling excess. So water shortages have become chronic. He points out the window to a pond that’s down 10 feet. “The last time that was full was in 2007.”

They eventually dug more ponds and keep tweaking the system so they don’t have to buy city water, but it’s a continuing worry. Like many ranchers that terrible winter, the Hutchinses had to cull a substantial portion of their small cattle herd because they didn’t have the grass, hay or water to sustain it. Several ranchers went out of business. The Hutchinses kept going. Indeed, despite the ups and downs, Rehoboth’s sales have grown every year.

The family has also been dogged by regulatory challenges because grass-fed, pastured animals didn’t fit the existing state and federal protocols. “The trail of regulatory obstruction started our first year,” says Robert. “I got a phone call from the meat safety inspection division of the state saying, ‘We’re gonna shut you down.’ We launched legislation to get a statute passed in the Texas legislature allowing processing on the farm.” He also has operated a Grade A goat milk dairy off and on over the years. Boutique farmers and ranchers are still fighting to be able to sell raw milk at farmers markets, a subject Robert calls “toxic” with lawmakers. But at least, he says, people are talking about it.

“Everything I do today requires everything I learned in business,” he says. “Agriculture is an industry. Anything that needs to be changed is ushered in from people on the outside. They aren’t stakeholders in the current system.” He has fostered not only legislation, but is an active advocate at farmers markets. Not so many years ago, before it moved to the Chestnut Square Historic Village, the McKinney market was in danger of being voted out of existence by the city council. Robert was part of an effort to marshal community support. Today the Historic McKinney Farmers Market is one of the area’s most successful.

At times, market discussions center on what constitutes “local.” Robert, for instance, gets his lambs from Oklahoma, aft er finding conditions less than optimal for sheep at Rehoboth. “You could do the same thing in West Texas,” he says, “but Oklahoma is closer. State boundaries do not define local and non-local.” He misses the sheep and their weed-clearing ability. But Rehoboth’s microclimate created too many problems, such as parasites during the wet season. He located a source in Oklahoma that raises sheep on pasture with no chemicals, and they are never wormed because reduced rainfall obviates the need.

Robert also is adamant about providing only non-GMO feed for his chickens, even though it costs more. “That’s one of the things that differentiates us: We use only feed from non-GMO grains that are also organic or in transition. …We have seen firsthand the damage from GMO grain and what it does to the internal organs of animals,” he declares. “We did a test: a ton of locally grown corn-GMO-soy feed and a ton of non-GMO. When we processed the non-GMO, the chickens had picture-perfect organs. With the GMO [chickens], while far better than conventional feed, we saw spots on the liver, lung disease and disease spots in the fat. They weren’t as healthy.” He’s not saying everyone would get the same result, but the experience persuaded him to adopt a non-GMO hard line.

As Robert and Nancy approach retirement and the children scatter from the homestead—he and Nancy now have nine grandchildren with three more on the way—he says one possible future for the ranch involves gradually scaling back. Or, a member of the family might step up to take over. But there’s still plenty fire in Robert’s belly. The ranch recently bought a diesel-powered farm car, and he’s so optimistic about the prospects of legislation allowing raw milk sales at farmers markets, he’s about to restart the goat milk dairy.

But he has one tiny beef. “Customers beat us about the head and shoulders when they can’t get eggs,” says Robert, brown eggs in particular being the hot commodity. “Brown egg layers lay less than white egg layers,” he says, “but it is pointless for me to try and convince customers that brown eggs are not superior to white eggs.” So he produces brown eggs because resistance is futile. “We try to break even. That’s our goal.”

VISIT REHOBOTH RANCH

Want to take a closer look at Rehoboth Ranch? The family holds ranch tours at 11 a.m. the first Tuesday of every month; a $20 refundable deposit is required. Go to rehobothranch.com. For info about winter farmers market hours, visit coppellfarmersmarket.org and chestnutsquare.org for McKinney. Texas Meats operates Friday and Saturday in Shed No. 2 at the Dallas Farmers Market.

KIM PIERCE is a Dallas freelance writer and editor who’s covered farmers markets and the locavore scene for some 30 years, including continuing coverage at The Dallas Morning News. She came by this passion writing about food, health, nutrition and wine. She and her partner nurture a backyard garden (no chickens – yet) and support local producers and those who grow foods sustainably. Back in the day, she co-authored The Phytopia Cookbook and more recently helped a team of writers win a 2014 International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Award for The Oxford Encyclopedia for Food and Drink in America.

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/