BELLA HAMPTON FARM, TWO CITY-DWELLERS’ PRIDE, IS TENDED WITH A BIG, OPEN HEART

PHOTOGRAPHY TERESA RAFIDI

On a Sunday in February, I drive south from Dallas for brunch in a modern farmhouse near the tiny town of Kemp, where I will be welcomed by Nestor Estrada and his husband Cesar Aragon, who recently moved to the countryside like tumbleweeds that have improbably taken root.

“It was crazy, but we did it!” Estrada tells me as he gestures in a way that takes in the plot of newly churned earth where they’ve scattered wildflower seeds that will bloom next spring. Technically, Estrada is referring to digging the adjacent pond—one of six deep pools they excavated with the help of neighborly grace and rented machinery. But his exclamation could be used to describe any number of things the couple has done in the last year and a half. It could, in fact, describe a way of life: it is crazy, but they’re doing it.

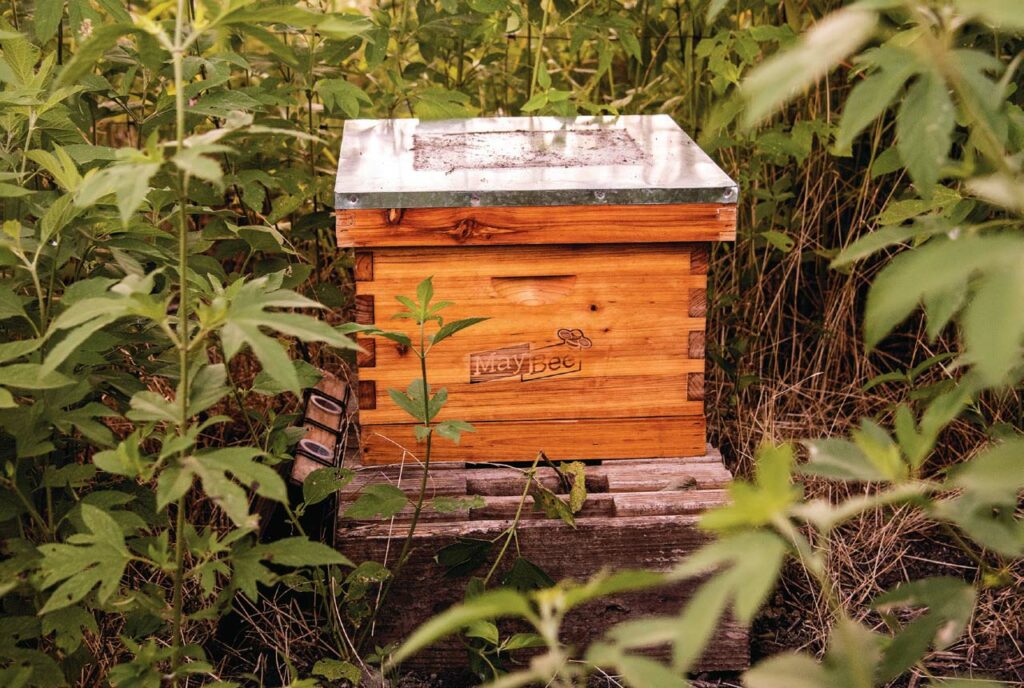

“This mantra, which led to the creation of Bella Hampton Farm, landed them the vision that now presents itself to me: one beehive with bees that pollinate the vegetable patch, a chicken coop with 150 laying hens and several dozen meat birds, several majestic turkeys, four dozen pigs, alpacas that reside amiably with Nubian goats, farther back three cows, three rescue donkeys, two ponies and four rescue horses, two Great Pyrenees,and closer in several other rescue dogs that gambol amicably.”

The whole menagerie is visible from the kitchen window of the home they bought and are in the midst of renovating to their taste—vibrant, eclectic, reminiscent of their roots in Guatemala, but also filled with art. Aragon, a graphic designer and art director for a multicultural advertising agency, chose vivid colors for each room. As Estrada makes coffee, they talk about their meeting 18 years ago in Guatemala, when they were in their 20s. Estrada was living briefly with his aunt while he recovered from drug addiction, and a birthday party eight hours away was the occasion for the couple’s encounter, a revelation that set their joint path. For nine years, they lived in Austin, where they owned several dozen chickens and sold eggs to family and friends. en home was a 1920 Tudor house in Oak Cliff. “We had an amazing garden in Oak Cliff.” Estrada says. at was where they first seriously discussed a plan to move to the country, a desire that stirred deep memories for Estrada of the Guatemalan coffee plantation his father’s family owned, where he had been close to the parcel’s animals.

“They’re living the dream,” Estrada says of the creatures in our view. If so, it’s because of his dreaming. When Estrada and Aragon went in, they went all in for what could go down in history as the apogee of passion-driven folly, this juncture of the agrarian and urban lives in the interest of rescuing animals, raising holistically, and building a haven.

“We moved to the country. We had a vision,” Estrada says. They naively thought it would be “bliss and a beautiful life,” Estrada says, laughing at their innocence. “There are a lot of ups and downs with this whole journey,” he continues. Because, while they’d tended a garden, they had no farming experience. “We’re both city people,” Estrada says. And, for example, “We don’t do mud.” Or hadn’t. But “try to walk all the way to the pigs with 100 pounds of feed in the morning, when it’s freezing and there’s rain.” When I meet them, they have just emerged from one of the coldest, muddiest winters— slogging with 50-pound hauls of hay—after a brutal summer, when cracks in the earth gaped so wide Estrada feared their horses might trip in them. “Emotionally,” he says, “it takes a lot. And financially, it’s like, ‘Oh, my God!’” That’s why they had to mark their hormone-free, heritage turkeys at $8 per pound last fall, selling them pre-order at the Oak Cliff farmers market where they also sell their eggs as well as their neighbors’ jellies and salsa. Estrada was a spin instructor, and his clients form a base for pick-ups at his crossfit studio in Dallas as well as at other venues and direct customer drop-off.

“Living the city life, you go to work and you go to brunch and you meet people [socially],” says Aragon, describing the urban-rural contrast. “Here you have a constant thing you have to do, and it doesn’t stop. So it’s hard to have a mental break.” It’s “like having hundreds of kids,” Estrada says.

Only one year into their endeavor, Bella Hampton Farm was invited to hold a booth at Chefs for Farmers. The eggs Estrada cracks for the brunch frittata range from olive green to pale blue and peach. The frittata is brilliant, sunshine yellow from their yolks. The jellies—strawberry-jalapeño, blueberry- jalapeño, and strawberry—we spread on toast with cream cheese are delectable. I’m cognizant of the animal husbandry behind our meal.

Estrada states bluntly and with gratitude, “We’re gay in the country, and everybody on this street watches out for us.” According to him, the community has been extraordinarily open and helpful. “So many straight men are like, ‘Whatever y’all need, we’re here,’” he says with deep appreciation. They were there when the ponds needed to be dug. They were there when the apocalyptic heat that assails Texas farmers and ranchers rent the earth with cracks. “I’m like, ‘What if a goat falls through the hole and breaks a leg?’” he recalls of his newbie concerns, born of profound empathy and fear that his safe-keeping would be inadequate. “And people were like, ‘It’s OK. They know it’s there.’” “It’s not your fault,” a neighbor told him when he was distraught at the loss of a goat kid. People sometimes ask Estrada and Aragon how many people they have tending the animals, and Estrada answers, “Just us—and the neighborhood.”

Thankfully, the duo learned of grants for first-time farmers. “A lot of people give up. Which is scary, because they’re small farmers,” Estrada says. There’s not enough community support at times.

Estrada acknowledges he has a rescuer’s heart. The two ponies came from a farm where they had been beaten with 2x4s, and it took Estrada 18 months to earn their trust. The 19-hand stallion that would have gone to slaughter—it had a lung infection and was scarcely breathing—is now a healed, towering black beauty. “You can’t let a magnificent horse go to die. He has a lot of life left to live,” he says.

Estrada and Aragon would like to set up a sponsor program as a way for people—perhaps city folk like they were—to live out a vicarious bucolic life and contribute to an animal’s well-being from afar. For $50 or $100 they could “own” a goat or an alpaca and bring treats when they visited. rough a herd-share program, customers wanting USDA-certified products could contribute to the processing of goat milk or have shares in a pig, specifying the cuts they would like of the hormone-free, antibiotic-free, pasture-raised meat.

The duo donates eggs regularly to Legacy Founders Cottage in Oak Cliff, a home for patients with advanced stages of AIDS. They would like to work with organizations that might bring special needs children to interact with the rescue animals at Bella Hampton. Eventually, they would like to open a bed and breakfast. We watch the piglets gallop across the yard, and I listen to Estrada and Aragon discuss whether they might get along with the dogs. They are working with the Bridge in downtown Dallas to pickup leftover food weekly, which they feed to the pigs, recycling around 100 pounds of vegetables, breads, and other foodstuffs.

“Ultimately, the goal is for the animals to live the happiest life they can. And yes, some of them have their last day. But they’ve lived happy their whole lives,” Estrada says. “I love animals and I love taking care of them,” he adds, and then, as though it weren’t abundantly clear: “So now I have a lot.” There are worse things, I think, as I gaze at this little paradise.

EVE HILL-AGNUS teaches English and journalism and is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She earned degrees in English and Education from Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Dallas Morning News, D Magazine, and the journal Food, Culture & Society. She remains a contributing Food & Wine columnist for the Los Altos Town Crier, the Bay-Area newspaper where she stumbled into journalism by writing food articles during grad school. Her French-American background and childhood spent in France fuel her enduring love for French food and its history. She is also obsessed with goats and cheese.

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/