Battling the Ongoing Drought

“Five out of the eight ponds are dry….. Two or three, we’ve had to fence off because the cows will bog down in the [muddy] water and die. We’re going to be talking about this one to our grandkids.”

– McKinney Rancher Matt Hamilton

At Matt Hamilton’s 600-acre family ranch just north of the Oklahoma border, the McKinney rancher-entrepreneur raises cattle for his grass-finished Genesis Beef. He gropes for words to explain how bad the Southwest’s drought has been. “In some pastures, I can stick my size 9½ boot up to my knee in the cracks in the ground,” he said in September. He couldn’t put horses or cows in those pastures. Too dangerous.

“Five out of the eight ponds are dry,” the stick-straight cowboy continued. “Two or three, we’ve had to fence off because the cows will bog down in the [muddy] water and die…. I told Nathan we’re going to be talking about this one to our grandkids.” Nathan Melson, who owns Sloans Creek Farm in Dodd City east of Sherman, partners with Hamilton, raising beef for Local Yocal Farm to Market, Hamilton’s butcher shop on the McKinney Square. “It’s been worse,” Hamilton drawled, “in ’56, ’81.” The old-timers still talk about 1956, he says. “That’s just part of the struggle. You gotta take the good with the bad. It’ll start raining. It’ll turn around.”

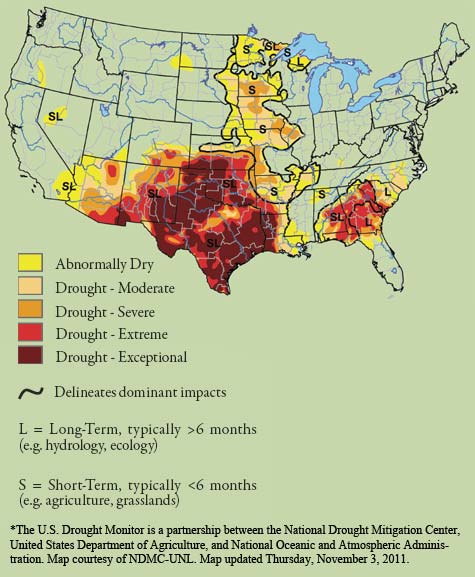

Miraculously, it did in early and mid-October – just enough to jump-start some ranchers’ winter forage. But not enough for everyone. Those who were bypassed by the storms are facing painful decisions. “This drought is ongoing,” says Dr. David Anderson, a Texas AgriLife Extension livestock economist. Whether ranchers can wring enough timely moisture from the skies to survive is anyone’s guess. Most of Texas and Oklahoma are under what the National Weather Service calls a D4 drought, an exceptional condition earning the agency’s most severe rating. The immediate culprit is a persistent La Niña over the Pacific Ocean. The weather service predicts “a weak to moderate strength La Niña is most likely during the Northern Hemisphere winter.”

“The total losses through August were $2.06 billion just for livestock,” says Blair Fannin, spokesman for the Texas AgriLife News Service, quoting the most recent figures available. “That counts supplemental feeding, culling herds, lost value, lost pasture.” Despite the grim picture, area ranchers who are committed to sustainably produced meat poultry and eggs fiercely believe in their methods and are not about to give up the fight. Even so, if rain doesn’t fall, the discussion may be different in the spring. For now, the ranchers’ goal is survival, having been brutalized not just by drought but a summer that was hotter than…well, you know.

When the drought and heat were at their fiercest, some ranchers started tapping into city or rural water to slake their animals’ thirst. “Our pond dried up,” says Robert Hutchins, whose Rehoboth Ranch near Greenville to the east went through a dress rehearsal for the current drought several years ago. “It costs me $1,000 a month to keep us in water,” he says. His take from the October rains? “We did several tenths of an inch,” not enough to make a difference.

In Grandview south of Dallas-Fort Worth, Jon Taggart got nearly seven inches on his 1,400-acre Burgundy Pasture Beef ranch from one October storm. That still put him 45 days behind on winter pasture, but “I’ve got a lot of grass going into a troubled time.” His herd is down to about 100, half its normal size, but he has enough land – with up to 40 separate grazing areas – so that no single pasture is overgrazed. Organic matter and mulch helped shade the dormant seeds through the hottest period, he says, part of a pasture management strategy that has helped him survive. “I had a tour group down here,” he says, “and the air temperature was about 104. I stuck a thermometer two inches into the ground in my neighbor’s overgrazed pasture, and it was 120 degrees. On our side, which was not overgrazed and had organic matter and litter, it was about 90 degrees.”

By mid to late summer, so many pastures across the Southwest were parched that there was an unprecedented run on hay. Cattle and horse ranches competed for a diminishing supply. “We’ve been hauling in hay for a couple of months,” says Oak Cliff-based Gary Nitschke, whose Nitschke Natural Beef from his family’s 3,000- acre Oklahoma ranch is sold in Whole Foods Markets. “It’s coming from as far as Indiana, Nebraska, Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee.” The most stressful moment for him was when he’d found some hay through the Internet, “and they didn’t deliver when they were supposed to. It got tight, down to a day or two when we had to feed less.”

“The hay is just not there,” says Hamilton, the McKinney rancher. “I had a deal on hay last night. At 7 p.m., it was $38 a bale for one load. At 7:45, it’s $45. At 9 a.m. this morning, it was $55 a bale. ‘Take it or leave it.’ I said ‘I’ll leave it.’” For one of his herds in nearby Melissa – Hamilton partners with several ranchers – he has taken the unusual step of collecting recycled vegetables from six grocery stores. “I get three 20-yard dumpsters a week,” he says. “We mix it with hay. In 48 hours, it becomes hay-vegetable silage.” He uses a similar technique with beans too small or imperfect to make a local manufacturer’s grade.

Culling has been unavoidable for many pastured-beef ranchers, although they’re doing their best to resist it. When Rehoboth Ranch failed to get appreciable rain from the October storms, Hutchins culled his herd by two thirds. “It will leave one bull and my ten best cow calves.” The rest went to auction. “We’re going to have beef through the winter,” he says. “Next spring there won’t be any.” To replace the lost income, he’s raising more pork, turkeys and chickens. “That’s my story next year: Eat more pork and chicken.” Melson is also switching to more pork and chicken as he trims his Sloans Creek herd.

Where do culled cattle go? Some are speeded through processing, such as Melson’s, which go to Local Yocal. The vast majority end up at auction houses, destined for slaughter that will flood the market with beef. “They’re sometimes running 24-hour auctions,” says Jackie King, who keeps three dozen head of cattle on 123 acres at P.O.P. Acres Ranch and Farm near Purdon, south of Corsicana. This creates a cascade of problems. In addition to the glut of beef, the animals often are not yet fatted to full market value, thereby reducing what ranchers can get. It also means there will be fewer springtime heifers, young cows yet to have their first calves, which are the rootstock for rebuilding a herd. Scarcity in the spring coupled with increased demand will drive up the price of heifers—and possibly the retail price of beef, too.

Some ranchers have simply moved their herds, as far away as Oregon and California, where they seek out like-minded sustainable ranchers with a bit of pasture to spare. Some, like Nitschke, have day jobs to support their operations. Taggart at Burgundy Pasture Beef, like Hamilton, has a butcher shop to augment his income.

Surviving the drought comes down to grit, creativity, networking and luck. Jimmy Sterling, whose ranch near Big Spring in West Texas normally supplies Taggart with heifers, recently sent 800 cows to Bill Wilson’s Sabine Ranch in south Jefferson County on the coast near Beaumont. “He’s got a lot of grass, and it’s pretty well managed,” Taggart says of Wilson’s operation. “The only reason he’s got room is Hurricane Ike,” which savaged the Texas coast in 2008. “The 17-foot storm surge came across his pasture. He lost 1,500 head, and he hasn’t built back up.” Too much water, too little water. “We lost all our buildings, all our equipment and half of our herd,” says Wilson. “There was no escaping it…. So while we were trying to swim our cattle to higher ground, ranchers in West and North Texas started sending us hay. Just started sending it. They helped us preserve the herd we had left.”

It wasn’t hard for Wilson to respond in kind to this year’s drought-stressed ranchers. “I don’t think any of these producers would make it without each other,” he says. “We’re taking care of Mr. Sterling’s cattle, and they’re looking good.”

photos by Carole Topalian

Last hay of summer.

Last hay of summer.

KIM PIERCE is a Dallas freelance writer and editor who’s covered farmers markets and the locavore scene for some 30 years, including continuing coverage at The Dallas Morning News. She came by this passion writing about food, health, nutrition and wine. She and her partner nurture a backyard garden (no chickens – yet) and support local producers and those who grow foods sustainably. Back in the day, she co-authored The Phytopia Cookbook and more recently helped a team of writers win a 2014 International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Award for The Oxford Encyclopedia for Food and Drink in America.

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/