photo: Stefani Austin

photo: Stefani Austin

“To see things in the seed, that is genius.”

— Lao Tzu, Chinese philosopher

Before making the arduous voyage to America in 1912, Dominic Antonio Defino, like so many other immigrants, tucked away seeds from his family’s garden. He would plant them in a new garden in Iowa, and the sweet, red peppers that grew there would forever remind him of his Italian roots.

Like a treasured photo album or a passed-down letter, heirloom seeds carry the stories of bygone times and faraway places. If we’re lucky enough to have them, they connect us to the unique flavors of fruits, vegetables and herbs savored by past generations. One hundred years after Defino’s arrival, his pepper plants still flourish in the gardens of his descendents, both in Iowa, and in Texas, where his great grandson, farmer Brad Stufflebeam, is carefully preserving this botanical link to his heritage.

“It’s a bell-shaped pepper like a chile ancho,” says Stufflebeam, whose Home Sweet Farm is located near Brenham. “It matures to red—a little thicker than an Italian frying pepper, but it’s super sweet.” Stufflebeam isn’t sure how to classify it; it’s so unlike any variety he’s ever grown.

The more he’s learned about his great grandfather, the more he’s realized the source of his own green thumb. The Defino family lived on the south side of Des Moines, known as Little Italy. Everybody had a garden, but his great grandfather, Big Papa, had one that filled an entire city lot and spilled into another. In the 1920s, Big Papa began planting on the city property beside the river. “He was down there farming two acres just because he loved to grow things,” says Stufflebeam.

Like a treasured photo album or a passed-down

letter, heirloom seeds carry the stories of bygone

times and faraway places. If we’re lucky enough

to have them, they connect us to the unique

flavors of fruits, vegetables and herbs

savored by past generations.

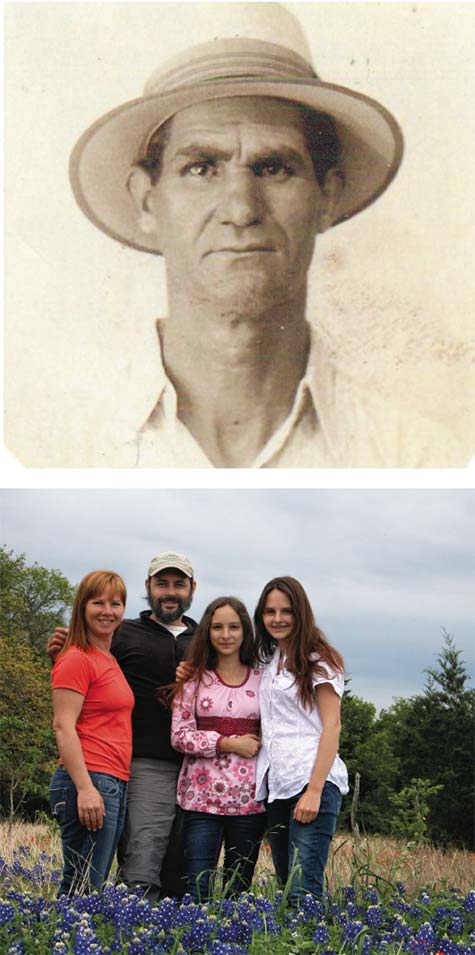

Top: Dominic Antonio Defino (1884-1978);

Top: Dominic Antonio Defino (1884-1978);

Bottom: Brad Stufflebeam with wife Jenny and daughters Brooke and Carina.

Big Papa died when Stufflebeam was only nine, but his seeds and story were passed down to the Texas farmer by his 89-year old great Uncle Armond, who’s been growing the pepper for over 35 years. Stufflebeam has shared the seeds with his father John Stufflebeam, owner of Sunny Side Up Farms in Weston, and his friend Mike Loggins, a landscape architect in Tyler. Loggins has incorporated the pepper into his designs, and, according to Stufflebeam, there are 20 or 30 families in Central and East Texas growing his ancestral plant. “Looking at other peppers, I can’t find anything similar to this. I feel like I’ve got something unique.” Stufflebeam hopes to submit his heirloom seeds to the Seed Savers Exchange in the fall.

With 13,000 members, Seed Savers Exchange is a non-profit organization that has been dedicated to preserving heirloom vegetables, fruits, flowers and herbs since 1975. The founders Kent Whealy and Diane Ott Whealy began their organization after Diane’s grandfather bequeathed her the seeds of a morning glory and a German pink tomato that had been brought from Bavaria by her great grandparents in the 1870s. At an 890-acre farm in Decorah, Iowa, the organization maintains thousands of heirloom varieties, which are exchanged through their catalog.

Native Seed/SEARCH in Tucson and Southern Seed Exchange in Virginia have also been promoting agro-diversity for decades, and many commercial seed companies, like Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds and Botanical Interests are proudly marketing non-GMO, heirloom varieties. Today’s renewed interest by backyard gardeners and small regional farmers is a reversal of the decline that began in 1950s as seed companies disappeared and plant varieties diminished with the advent of corporate agriculture.

Seed Savers Exchange member Reed Baize of Oklahoma has contributed seeds saved from a tomato variety cultivated by his East Texas grandfather Charles Herring. “I felt that it was time to share these and not just keep them in one backyard,” says 29-yearold Baize. The Charles Herring-Porter is a dark pink, plum-shaped tomato that Herring, a Gatesville businessman, spent four decades developing.

Baize, who inherited his grandfather’s tomato obsession, describes the Charles Herring as a variation that’s extremely hardy, just like his grandfather, who spent his early years picking cotton. “This tomato keeps on going when the other varieties have quit,” says Baize.

“I’ve tested them out against regular Porters, and this one grows at least six inches taller.”

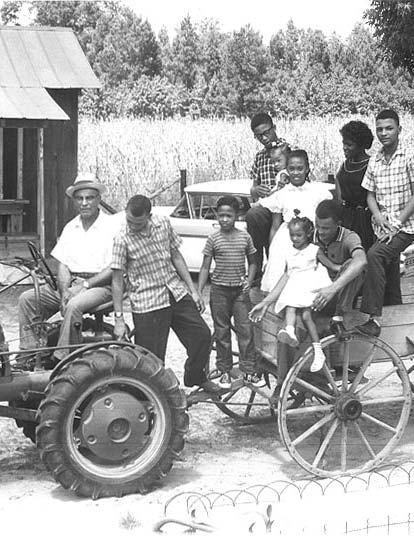

A.T. Odom seated on tractor with grandchildren

A.T. Odom seated on tractor with grandchildren

Family Reunion, 1949

Family Reunion, 1949

Mrs. Lillie Shankle White

Mrs. Lillie Shankle White

Baize’s pre-school aged daughter loves to spend time in the garden with her dad, and he hopes that she will carry on the tradition of planting. “The problem with heirlooms,” he says, “is that varieties are lost every year because people die without sharing them. And then they’re gone.”

Gardener Allan Jones of Rusk has been a member of Seed Savers Exchange for 20 years. Shortly after his mother died, he spotted a hand-labeled Mason jar of Southern peas she had saved. It had been a gift from one of their neighbors. He remembered the Bowden family’s garden, and his mother’s love of one particular pea that grew there. “I’ve been growing them ever since,” he says. The J.B. Bowden Old Time Speckled Pea is available on the Seed Saver Exchange along with other varieties Jones is collecting.

About two miles from where she was raised, 85-year-old Lillie Shankle White shells purple hull peas in her backyard. Starting in the cool of the evening, she puts up a bushel each day before bedtime. “I sit up till 12 or one o’clock, till I get ’em up.”

Shankleville, about an hour southeast of Lufkin, was founded by her great grandparents, Jim and Winnie Shankle, freed slaves who began purchasing land here in 1867. Mrs. White, the mother of eleven children, embodies a certain spirit that has empowered the community for generations. She has worked the land since she was a young girl. Her garden may be a little smaller this year, but she has not slowed down. She’s got peas, two rows of collards, one row of turnips and a row of mustard greens. These days, her son plows it up for her, but she still plants by hand, the same way she did when she followed behind her father’s mule.

“I’m still piddlin’ in the garden,” she says as she begins to explain the way it was. She remembers how they grew everything from peanuts to sweet potatoes, cane, corn, okra, pinto beans, butter beans and even rice. They raised chickens, hogs, cows and goats. “You name it, we raised it. We didn’t buy anything but meal and flour.” She saved seeds for 60 years, but she’s finally passed that task on to a new generation.

“I call it the good old days,” she says, with a laugh. “There’s still nothing like those purple hull peas.”

Lareatha Clay sits on the porch of her grandparent’s home in Shankleville

Lareatha Clay sits on the porch of her grandparent’s home in Shankleville

(photo by Will van Overbeek/TxDOT)

TEXAS PURPLE HULL PEA FESTIVAL

The 1st Annual Texas Purple Hull Pea Festival will be held in the historic freedmen’s community of Shankleville on June 21. The daylong event will feature pea picking, pea shelling and pea shooting contests, as well as classes in growing, cooking and preserving peas. There will be musical entertainment, a farmers market and an afternoon symposium on the culture of farming and food in Deep East Texas. In partnership with the University of Texas- Austin’s American Studies Department and Foodways Texas, the Shankleville Oral History Project is documenting the recollections and stories of those who were raised here.

Shankleville is named for founders Jim and Winnie Shankle, the first African Americans to own land in Newton County following emancipation. Born into slavery, their story began on a Mississippi plantation, where they lived together until Winnie and her three children were abruptly sold off to a Texas planter. Determined to find her, Jim escaped and traveled over 400 miles on foot, walking through the night and foraging for food to avoid being seen. He crossed the Mississippi and journeyed into East Texas where he eventually found Winnie drawing water at a spring. After Jim spent days in hiding, Winnie was able to convince her new master to buy Jim. Reunited, they had six more children.

At the Civil War’s end, Winnie and Jim, along with their son-inlaw Stephen McBride, began buying land and amassed over 4,000 acres in Newton County. Shankleville grew to prosperity and in its heyday included a cotton gin, a gristmill, sawmills and schools, including McBride College (1883-1909). Since 1941, their descendants have held an annual Shankleville homecoming.

Descendant and festival organizer Lareatha Clay is a Dallas business consultant, who serves on the board of the Dallas Arboretum. A former commissioner of the Texas Historical Commission, she helped found the Shankleville Historical Society in 1988. Clay developed her love of history while shelling peas and listening to stories on the porch of her grandparents Addie L. and A.T. Odom. Their 1922 Shankleville homestead, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is the site of many of the festival’s activities. The house and its outbuildings sit on a hill above the spring where Jim and Winnie were reunited.

Texas Highways magazine named Clay one of their Extraordinary Texans of 2013 in part for her diligence in documenting the Shankleville story. In an interview she said, “Some folks think historic preservation is only for the mansions of famous people, but everyone’s history is worth preserving. Even a modest house and a modest story are worth remembering.” The same could be said for the little purple hull pea.