Patrick Wright, farm manager

Patrick Wright, farm manager

Photography by Robert Strickland

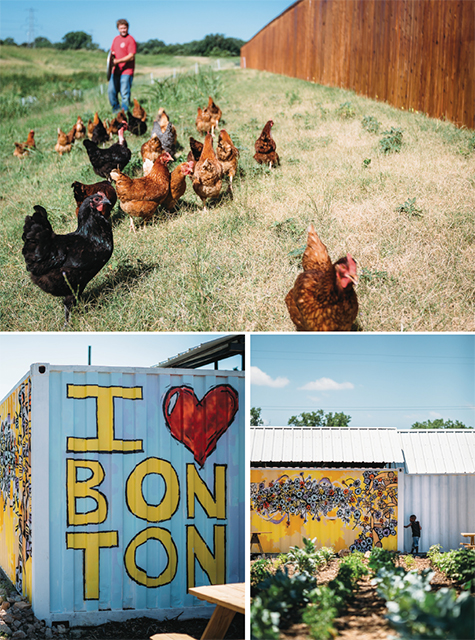

At first glance, Bonton Farms seems like a lot like other farms. There are rows of tomatoes, peppers and some beleaguered collard greens holding on in the Texas heat. There are goats, chickens and turkeys in search of shade. You can hear the birds sing and the wind move through the trees.

But listen more closely and you’ll hear other sounds. Music coming from the open windows of cars. Kids laughing and playing under a big shade tree. The low hum of traffic from nearby U.S. 175. The sounds of an urban neighborhood.

Sandwiched between a new affordable housing complex and the Trinity River levee, the farm is located in the Bonton neighborhood of South Dallas, an area devoid of grocery stores, a food desert where access to fresh vegetables, fruits, eggs and meat has been nonexistent. Until now.

The people who congregate at Bonton Farms are working to change that. And it is the people who set the farm apart. The first person you’re likely to meet is Patrick Wright, the farm manager. He’ll wave you over and greet you with a firm handshake and big smile. Wright is in charge of the animals, and it is clear he loves his work on a level most people can only dream about.

But he hasn’t always been the happy and friendly person he is today. When Wright first came here, he was struggling to find a reason to live. “I was broken and in despair. I didn’t like the person that I had become,” he says. “I didn’t feel like I was a good son, father or friend.” Past choices made it difficult for him to find work and ultimately hope.

“When people fully invest in this thing,

radical changes happen.”

— Daron Babcock, founder, Bonton Farms

Top: Bonton chickens foraging near Trinity River

Top: Bonton chickens foraging near Trinity River

levee. Bottom: Fence paintings by local artists.

While every person at the farm is unique, many of their stories share common themes. A history of drug and alcohol abuse, sometimes coupled with prison time, means a past that allows few options. When life’s hurdles seem impossible, that’s when they find themselves at the door of Daron Babcock, the farm’s founder.

Babcock created the farm as Director of Urban Missions for H.I.S. BridgeBuilders, a faith-based organization focused on alleviating poverty. He understands the way poverty and addiction shatter lives and believes that the only way to mend those fractures is to restore an individual’s relationships with God, self, others and creation. For eight hours a day, the farm provides a means to repair those connections. “When people fully invest in this thing, radical changes happen,” he says.

In 2012, when Babcock left his career in private equity and made the unlikely move from Frisco to the Bonton neighborhood, he had no intention of starting a farm. He just knew it was the place he was supposed to be. “When you believe with everything you have that you are supposed to be somewhere, it doesn’t really matter. I was coming no matter what.”

Babcock connected with those in need because of his own struggles with addiction and loss. “If I hadn’t been through all that, I don’t know if I would have been able to earn credibility with the community. It isn’t possible for me to fully understand what people here face, but I do have a small glimpse. And that glimpse has been enough to allow me to make a connection.”

Babcock helps those with a difficult past remove the barriers that keep them from finding work. This includes practical tasks, such as using the farm to establish a recent job history, and also on broader goals, like discovering hopes and dreams. “When I got here, I would ask them— ‘If you could start all over, what would you do with your life?’ For six months, I didn’t get an answer because they all believed that dreams only led to disappointment.”

The farm is a perfect platform for life lessons like patience, perseverance and acceptance. “Whether we realize it or not, at the end of the day we’ve all received instruction and support,” says Babcock. “Every day we make some forward progress from where we were.”

“Farm work is therapeutic for me,” says Wright. “The animals teach me how to be compassionate. They depend on me. I have to feed them and give them a clean place to stay. And in return, when they hear my voice, they run and greet me. They can be little rascals, but just because I’m stronger doesn’t mean I can bully them. They teach me all kinds of virtues every day.”

“The farm is a perfect platform for life

lessons like patience, perseverance and

acceptance. Whether we realize it or not,

at the end of the day we’ve all

received instruction and support.”

— Daron Babcock

Daron Babcock, founder of Bonton Farms.

Daron Babcock, founder of Bonton Farms.

Neighborhood children also find themselves drawn to the farm animals and the sandy soil. Mariyah Martinez and Sierra Leonard are some of Bonton’s most faithful young volunteers. They help Wright give goat “pedicures,” which is a glamorous name for trimming hooves. Martinez loves every minute of it. “I have a lot of love and compassion for the animals. My favorite thing is to feed the baby goats. But sometimes the goats try to head butt us so we have to be careful.” No matter why they love spending time on the farm, they both agree on their favorite summer vegetable: cherry tomatoes.

Before there was a farm, there was the growing realization that an alarming number of Babcock’s neighbors were sick with complications from chronic disease, largely due to poor diets. With little access to personal vehicles, getting to a grocery store meant hours spent on the bus. Throw in the trappings of poverty plus the loss of familial food traditions over the years and you have the makings of a full-blown community health crisis.

Babcock knew that creating access to nutritious food was only the first step, but it was an area he and his volunteers could improve with little outside help. First he started a garden in his own yard, and then in January of this year that garden was moved to the end of Bexar Street and a farm was born.

“Rather than fight with nature, we want to work with it,” he says. “Before the levee was built this was a flood plain, so our soil is 70 percent sand. That means we have really got to amend and work to improve its quality. That is a process and a commitment that takes years.”

Blake and Barbara Roberson

Blake and Barbara Roberson

The farm currently sells 90 percent of its produce at farmers markets and to restaurants like Café Momentum and Garden Café. Bonton residents have a chance to buy produce every other week at a small neighborhood market, but Babcock knows when it comes to getting people to actually cook and eat fresh produce, access isn’t enough. When he talks about his plans and dreams for the farm, which include an onsite commercial kitchen for community health and cooking classes, one can see his long-term commitment to the land and people here.

The farm enjoys the support of a variety of volunteers and faith-based organizations from all over the Dallas area. Though the volunteers are coming to help change Bonton for the better, Babcock hopes that they leave fi nding themselves changed.

“Dallas is really a tale of two cities,” he says. “I hope that our story helps more people realize how true that is. When you become aware of a wrong, you have to make a choice: to ignore it or do something about it. For me, my faith requires me to respond. I hope other people will choose to do their part. We aren’t meant to isolate ourselves while those around us suffer.”

Babcock knows that just like amending the soil, community change is slow-going and incremental. “It is one life at a time. If I were on my deathbed and someone told me that because Patrick and I became friends his life was changed for the better, then all this will have been worth it.”

For more information, follow them on Facebook or go to bontonfarms.com.

LIZ GOULDING teaches biology at El Centro College and is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She has previously worked for Urban Acres, Holistic Management International and served as chapter leader for Slow Food Dallas. She is currently focused on the stories behind local food producers and artisans, and the ways that food unites families and communities.

- Liz Gouldinghttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/lgoulding/

- Liz Gouldinghttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/lgoulding/