Chef Graham Dodds takes the

message farther, deeper, tastier

Photography by Joy Zhang

Chef Graham Dodds wears his heart not on his sleeve, but on his gimme cap, emblazoned with the words “Make Cornbread Not War.” After stints from Oregon to Switzerland and with more than a few notable Dallas chefs (Sharon Hage, Stephan Pyles), Dodds finally has a restaurant of his own—a platform where he can shout his farm-to-table credo from the rooftop.

But he’d rather put it on the plate at Wayward Sons, and use his shiny new Lower Greenville spot as a bully pulpit to proclaim the virtues of plant-centered eating and the value of relational restaurateuring—a 25-cent phrase for the way he works with growers and employees that goes beyond the farm-to-table meme. You might say it’s in his bones. Or, more accurately: in his beets.

At Wayward Sons, meat doesn’t define

the menu. What’s growing locally does.

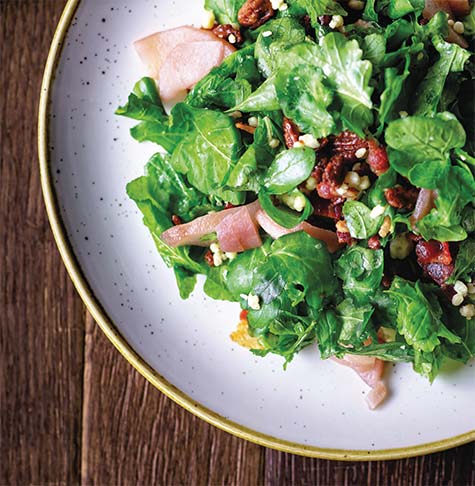

Salad with Comeback Creek arugula and Eagle Mountain blue cheese

Salad with Comeback Creek arugula and Eagle Mountain blue cheese

Partners Phil Schanbaum, Graham Dodds and Brandon Hays.

Partners Phil Schanbaum, Graham Dodds and Brandon Hays.

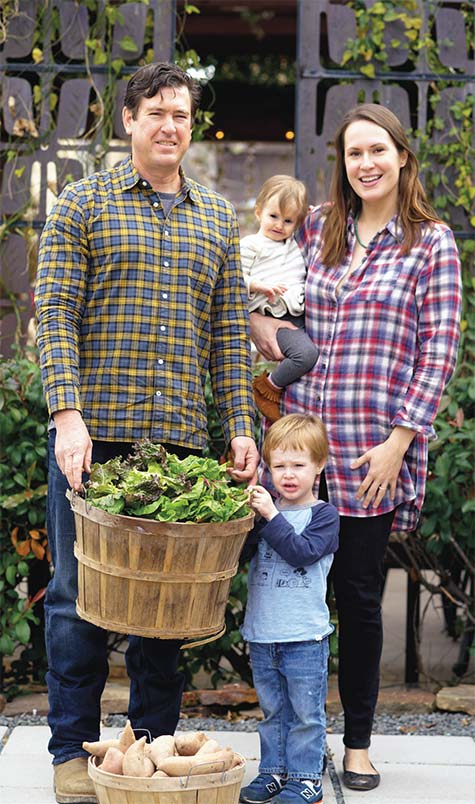

“He cares about the people growing and raising the food he cooks as much as he values the diners who will eventually be eating it,” writes supplier Aliza Kilburn in an email. She and her husband John own Comeback Creek Farm near Pittsburg and operate The Farmer’s Wife storefront in Mt. Pleasant.

“One of the greatest things about working with Graham,” she says, “is that rather than come to us with a laundry list of exotic vegetables and herbs he’d like us to grow, he counts on us to be experts about what will and won’t grow well in our area…. He has a practical understanding of the realities of farming in Texas…and this understanding heavily informs how he writes his menus, giving him the flexibility to actually work with what we produce in a given season.”

Farm-to-table before it became cliché, Dodds went so far at Bolsa in 2008 as to shun walk-in cold storage. But isn’t everyone farm-totable these days? In a word, no. It’s as common as green-washing for a restaurant to start out sourcing locally, then gradually back off as menu and bean-counter demands put the pressure on. In some instances, Dodds notes, farmers have had to request that their names be removed from menus where chefs no longer buy from them.

At Wayward Sons, meat doesn’t define the menu. What’s growing locally does. Dodds pulls in seasonal produce from small, local farms and his own on-site garden even in the tough days of winter, adding animal proteins from local producers where possible. Dishes run to chef-driven comfort foods such as chicken and dumplings, arugula salad with poached pears and blue cheese, buttermilk biscuits with Mom’s preserves, and cornmeal-dusted catfish. His garden “charcuterie” is famously meat-free. So is his vegan wild mushroom tamale.

Dodds is quick to note he’s not alone in steering plates away from animal protein. “Matt’s menu at FT33—meat’s almost an accompaniment,” he says, calling out Matt McCallister. “Bolsa stayed on that course.” He was the founding chef at the Oak Cliff restaurant, where Matt Balke is executive chef now. “I think Nonna does a good job of it,” he adds, acknowledging chef Julian Barsotti.

Back in 2001-02, working at 1,400-acre Shelburne Farms taught Dodds to look at animals as more than a tenderloin count in a box. “We raised beef, lamb, pork,” he says. Every Monday in the fall, they’d harvest whole animals. “We had to cut them up. I’d never done that before. You go to the barnyard and pet the animals and then they’re on the plate.” After that, the chefs at the Vermont property felt bad if they overcooked and ruined a piece of meat. “It’s the simplest thing,” Dodds says. “We put a face to it.

People didn’t detach.” At Wayward Sons, the animal protein that does show up on his plates comes only from humane, sustainable producers, he says, something deeply embedded in his values. The shift toward plant-focused plates can be contentious in a meat-centric town. Originally, Dodds lobbied to omit pork entirely from the Wayward Sons menu, in part because he’s come to see pigs as more sentient than other animals. His two partners at This & That Concepts, Brandon Hays and Phil Schanbaum, thought he needed to offer at least one pork dish. The duo—one vegan and the other Jewish—“felt we had to have it,” Dodds says. He said yes, then said no and the ribs are off the menu. For now. It was one of his bestselling dishes. And the friendly discussion continues.

“Our feeling about him from the beginning was that he was one who really ‘walked the walk’ when it came to using locally grown produce and actually supporting small farms,” says Aliza Kilburn. “I have a full commitment to supporting the [farm] family,” Dodds declares.

For instance, he buys pricey organically grown, free-range eggs from Mac McCarthy, a Vietnam vet and former Amtrak engineer who owns Dis & Dat Farm near Corsicana. McCarthy started selling at the Dallas Farmers Market, but area chefs like Dodds and Matt Ford (now at Americano) quickly monopolized his production.

They also buy his strawberries, watermelon and cantaloupe in season. “He (Dodds) recognizes his suppliers,” McCarthy says. “When he went to New York for James Beard [Dinners at the Beard House], his menu had our name on it. I was proud of that.” Dodds presented a dinner at the prestigious venue a year ago while he still was chef at Hibiscus.

“We’re friends,” Eric Tippett says simply—half of the husband-wife team that owns Caprino Royale micro goat dairy near Waco. “I wouldn’t care if he bought cheese from us or not.”

But he does buy their cheese and has done so since his earliest days at Bolsa when the producer cold-called on him. Caprino Royale was then a start-up fresh chevre operation, and Bolsa became their second customer after Fearing’s. Today Dodds buys their aged Spanishstyle cheeses, as Tippett and wife Karen Dierolf switched to an allaged lineup 18 months ago. Most of their production goes to chefs, but a selection of their cheeses is available retail at both Scardello Artisan Cheese locations.

“Graham is the kind of guy who builds good relationships,” Tippett says, “and they [growers and producers] follow him.” That extends to his staff, too, Tippett adds. “He’s willing to teach people,” the goat farmer says. “If he likes you and thinks you have potential, he’ll take the time to teach you. Graham notices.” A lot of good chefs do this. But Dodds has taken this desire to give back a step further than many, most recently opening his kitchen to the new wave of Middle Eastern immigrants, whom he describes as the next great worker pool.

“We’ve got a Syrian guy,” Dodds says, “two Iraqi guys and an Iranian— all part of the kitchen crew. All work so hard. It’s a better life for them and enables them to have a job and support a family. They come to me with no experience. They pay attention. They’re supersmart. And there are benefits for us. We have loyal employees who stick with you, show up and are appreciative. I love having a diverse group in the kitchen. It’s exciting.”

“I have a full commitment to supporting

the [farm] family,” Dodds declares.

Comeback Creek Farm’s John and Aliza Kilburn with children Sam and Juliette

Comeback Creek Farm’s John and Aliza Kilburn with children Sam and Juliette

This came up when Dodds was explaining the back-and-forth over pork. He freely admits that some dishes cry out for bacon. “You need that smoky, salty, fatty bacon in some of the classic dishes,” he says, “like frisee and lardons.” His solution: He makes beef bacon inhouse and jokingly told his Syrian cook, “You can finally eat bacon.”

Even avowed vegans get an itch for meaty goodness, especially if they are Texans who grew up with barbecue. At Dodds’ first vegan dinner—which, he says, sold out more quickly than any dinner ever—he wanted to continue showing veggies in new ways without smothering them in ersatz protein or dairy. Because he loves barbecue, he came up with the idea of smoked root vegetables, including burgundy carrots and celery root, using his house-made barbecue rub. “After they were smoked and roasted, they had a crust just like brisket,” he says. “Everybody loved that dish.”

By now, Dodds’ back story is familiar to foodies: Born in Fort Worth, he grew up in Hurst. His mother was English (a naturalized U.S. citizen), and he spent many summers visiting his English grandparents, where he learned about gardening and picked up his penchant for beekeeping. (He’s considering a hive for Wayward Sons’ rooftop.) His mother, who lives in Colleyville, still makes jams and jellies for him—and he freely admits they’re better than he can make. His chef sense and immersion in farm-to-table began in 1995 with studies at Le Cordon Bleu in Portland, Ore., where he also worked with Greg Higgins at Higgins Restaurant and Bar. There, sustainability and stewardship are a way of life. You could say the lessons stuck with Dodds.

“One of the jobs of a chef is to educate, to take a stand,” Dodds says. “I firmly believe a plant-based diet is much more sustainable, not just for our bodies but for the environment…. It’s time to start focusing on that.”

KIM PIERCE is a Dallas freelance writer and editor who’s covered farmers markets and the locavore scene for some 30 years, including continuing coverage at The Dallas Morning News. She came by this passion writing about food, health, nutrition and wine. She and her partner nurture a backyard garden (no chickens – yet) and support local producers and those who grow foods sustainably. Back in the day, she co-authored The Phytopia Cookbook and more recently helped a team of writers win a 2014 International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Award for The Oxford Encyclopedia for Food and Drink in America.

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/