HIDDEN HANGAR VINEYARD AND WINERY

When considering a name for her new Denison winery, Stormy Cansler was inspired by the rich history of her property. The site was once Gray Field, Grayson County’s first airfield, which opened in 1928 at the advent of aviation.

“Everyone knows about Perrin Field, but Gray Field came first,” says Stormy. “This was once a hoppin’ and boppin’ spot.”

That’s hard for me to imagine as I relish the tranquility of the Hidden Hangar vineyard at sunset. Light is reflecting off the lake, tinting the leafy vines in gold. All is quiet except for the vineyard dogs, Malbec and Riesling, panting as they dart in and out of the verdant rows in pursuit of a ball.

There are no barnstormers flying overhead today as there were in the 1930s, during the days of open cockpits and grass runways, when everyone wanted to fly.

“On Sundays, the Old Airport Road was packed,” she says, pointing to the edge of the vineyard. “People came to watch planes take off, and if you could scrape up a quarter, you could ask to tag along. They would fly you over Texoma—these so-called pilots, some of whom had only been up once or twice. They were flying by the seat of their pants.”

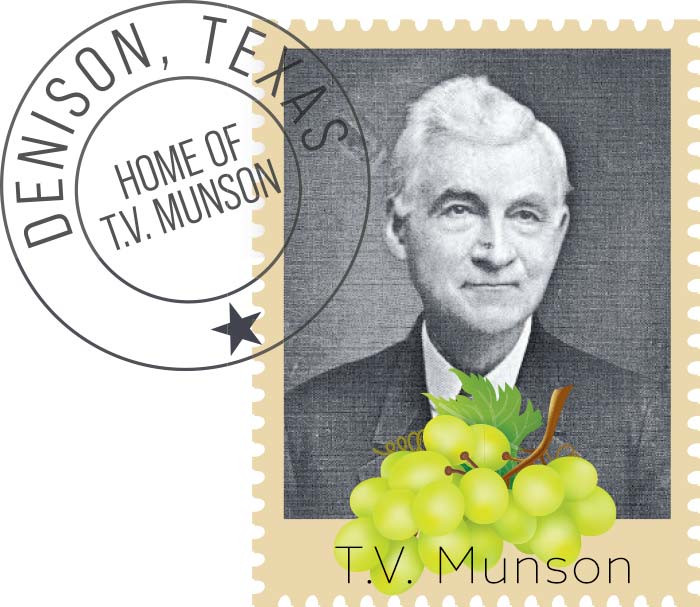

My thoughts drift to T.V. Munson, and I imagine how he would have loved both scenarios—the peace of today’s vineyard and the buzz of yesteryear’s bi-planes. Though he missed Gray Field’s opening by 15 years, he was fascinated with flying machines, which were all the rage a er the Wright Brothers took to the air. A Renaissance man and visionary, Munson loved to invent things. e framed sketches of his “Safety Flying Car”— a rudimentary helicopter with a parachute—hang next to a vintage telephone at “Vinita,” his restored home a short drive from here. Munson was preparing to submit the design to the U.S. Patent Office when he died in 1913.

This vineyard is a dream Stormy inherited from her mother. Her parents, John and Martha Lattimore, had planned to share the project, but Stormy’s father passed away before they could begin. In 1990, when Grayson College Viticulture faculty offered to help, Martha moved forward. She thought a vineyard would make a very pretty front yard, but when the vines finally started producing, she turned it into a business, entering into an exclusive contract with Messina Hof Winery in Bryan, while donating a portion of the harvest to the college.

In 2017, when Stormy took the reins, she made the momentous decision to add a winery. “My husband was 100 percent against it,” she says with a laugh. (Richard Cansler has his own connection to aviation. He is a long-time recreational pilot and owns a plane.)

Steadfast and determined, Stormy took classes at Grayson College and Texas Tech, and read every book she could find. “I’m a voracious reader. You educate yourself and then put yourself in God’s hands.”

Unlike most start-up winery owners, she was graced with an estate vineyard nearly 30 years in the making. Today, there are 50 acres of riesling, syrah, petite verdot, malbec, cabernet franc and cabernet sauvignon, Old World Vitis vinifera that most growers consider unsuitable for Texas.

But as T.V. Munson has proven, the Texas terrain is full of surprises.

Hidden Hangar is a mile south of the Red River and part of the Texoma AVA (American Viticultural Area), one of eight grape-growing regions in Texas notable for their unique soil and climate.

The vines are planted according to their needs. The cabernet franc sprawls across a rocky hill near the lake. The malbec grows on the east side of the hill, protected from the late afternoon sun. It gets a strong southeasterly breeze in the summer to help satisfy its need for a 20-degree cool-down each day. Riesling, the high-maintenance child, expects to be coddled, though it doesn’t seem to mind cold weather.

A deep 11-acre lake provides the vineyard’s water source. The water in North Texas can be too salty for grapevines, says Stormy. The lake allows them to correct the water’s pH and provides a back-up in times of drought. “We try to be forward-thinking,” she says.

Committed to hiring a top-notch winemaker, she put an ad in a major publication and was shocked by the response. “Seventy-five people from all over the world wanted to come to Denison!”

They chose Chicago native Mark Schabel, a graduate of the U.C. Davis Viticulture and Enology program with 21 years of experience in various locales in California and New Zealand. Before coming to Texas, he worked for six years in the Temecula Wine Region of Southern California as a consultant and as the winemaker for Ponte Winery.

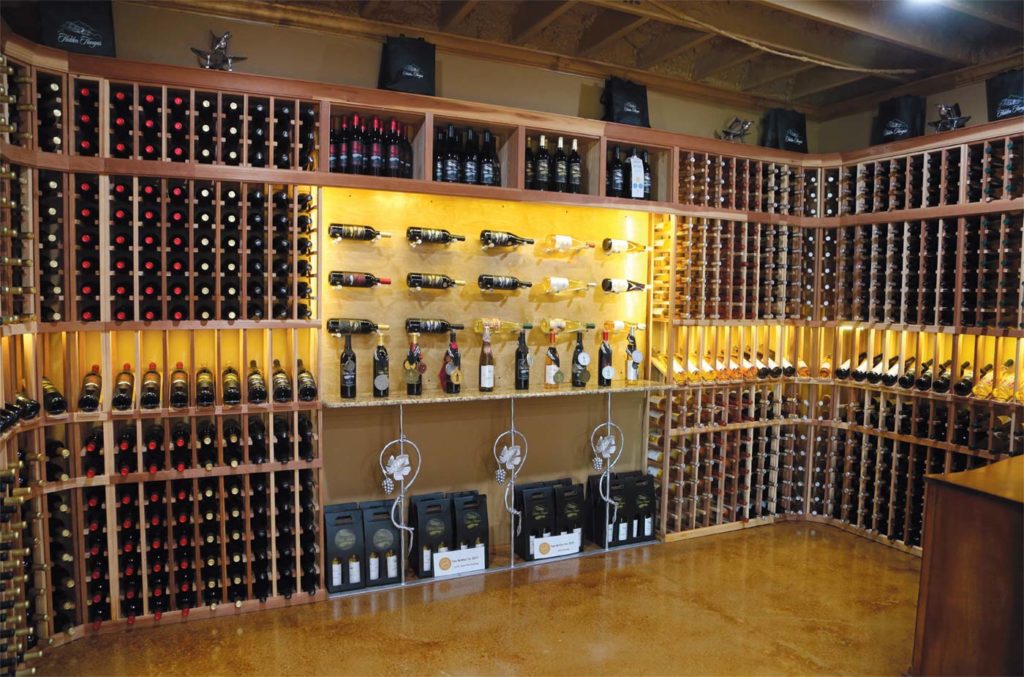

Hidden Hangar Winery opened in 2019, and to everyone’s delight and surprise, their wines quickly began garnering awards. In 2021, their cabernet franc took Double-Gold and Best in Class at the Houston Rodeo’s International Wine Competition.

Next came recognition for their syrah and their malbec. “People say you can’t grow malbec here. Well, our malbec just won silver in San Francisco and gold in Houston,” says Stormy. “I’d say we can grow malbec.”

Close to home, the Likarish brothers at Ironroot Republic are singing the praises of Stormy’s riesling, deeming it the perfect base wine for the distillery’s brandies. They sampled it with a group of Cognac producers who were blown away by its exquisite qualities.

“I want to grow the best Texas grapes and make the best Texas wines,” says Stormy. “In a short amount of time, we’ve put a lot in place to do that.”

When dreaming up names for their wine blends, they’re the ones who bestow the honors. Two of their reds recognize women’s contributions to the country during WWII. Riveter Rosie is named for those who worked in shipyards and factories, while Fly Girls salutes the WASP (Women Airforce Service Pilots), a civilian air corps of 1,100 women who volunteered for service. They flew military aircraft across the country, towed aerial targets for gunnery practice and made test flights, all to free male pilots for combat.

“They learned to fly on their own dime,” says Stormy. “They pulled their hair back and dressed like the guys. They were cutting-edge and daring. It wasn’t until decades after the war that the government recognized their service.”

This spring, at the WASP 80th Anniversary Celebration in Sweetwater, Hidden Hangar wines were served, including Fly Girl, which has three female aviators adorning its label.

“This vineyard was started by a woman and is being carried through by women,” says Stormy. “We were proud to be included.”

As a kid, TERRI TAYLOR refused to eat her vegetables. Her veggie-phobia was cured in 1977 when she spent eight months working on farms in Norway and France. She studied journalism at UT-Austin and received a master’s degree in liberal arts from SMU. Her short story “Virginia” can be found in Solamente en San Miguel, an anthology celebrating the magical Mexican town of San Miguel de Allende. She has written for Edible DFW since its inaugural issue in 2009. She became the magazine’s editor in 2010 and is the editor of Edible Dallas & Fort Worth: The Cookbook.