Foraging in the City

Photography Teresa Rafidi

Have you ever eaten a pecan that has fallen from a tree? Made grape jelly from wild Texas grapes? Have you plucked a mulberry, plum or other ripe wild fruit that has been warmed by the summer sun? Growing up in North Texas, these were all things I experienced as a child, decades before I knew what the term “foraging ” meant.

The challenge to source the freshest local ingredients has led some North Texas chefs to expand their palates and pantries by venturing into the wilder parts of our area. Foraging is the ancient practice of searching for and gathering uncultivated plants and fungi that have been considered food for thousands of years.

In many countries across the globe, foraged food is still essential. In North America, uncultivated native plants dominated the cuisines of indigenous peoples and early pioneers alike. It wasn’t that long ago that local families utilized wild food out of necessity. My father still remembers my great-grandmother cooking poke salat, a wild green—delectable when safely prepared. Most of us have foraged for food at some point in our lives without even realizing it.

As an adult, I couldn’t imagine a week going by where I don’t snack on something foraged, even in our highly urban areas.

Dallas chef David Peña feels the same way. He began a dedicated study of foraging and the value of edible wild plants only five years ago. And although he doesn’t consider himself an expert, he is already one of the most knowledgeable foraging chefs in our region. Much like myself, his passion for foraged food started as a child with a love of the outdoors. He was always fascinated with plants, insects and rocks. Whether camping or exploring during family gatherings, Peña was a budding naturalist.

“I remember growing up eating pecans in my great aunt’s backyard,” recalls Peña. “My brothers and I would give them a shake then smash them open with a rock and eat them raw. That always stuck with me.”

Foraging is the ancient practice of searching for and gathering uncultivated plants and fungi that have been considered food for thousands of years.

Palmer’s amaranth (left), Amaranthus palmeri, produces leaves that can be used like spinach, and seeds that can be a grain substitute. Elderberry flowers (center), Sambucus canadensis, can be eaten raw, fried or made into a sweet-smelling liqueur. When made into a jelly or a syrup, the cooked berries are used to combat flu symptoms. Black walnut (right), Juglans nigra.

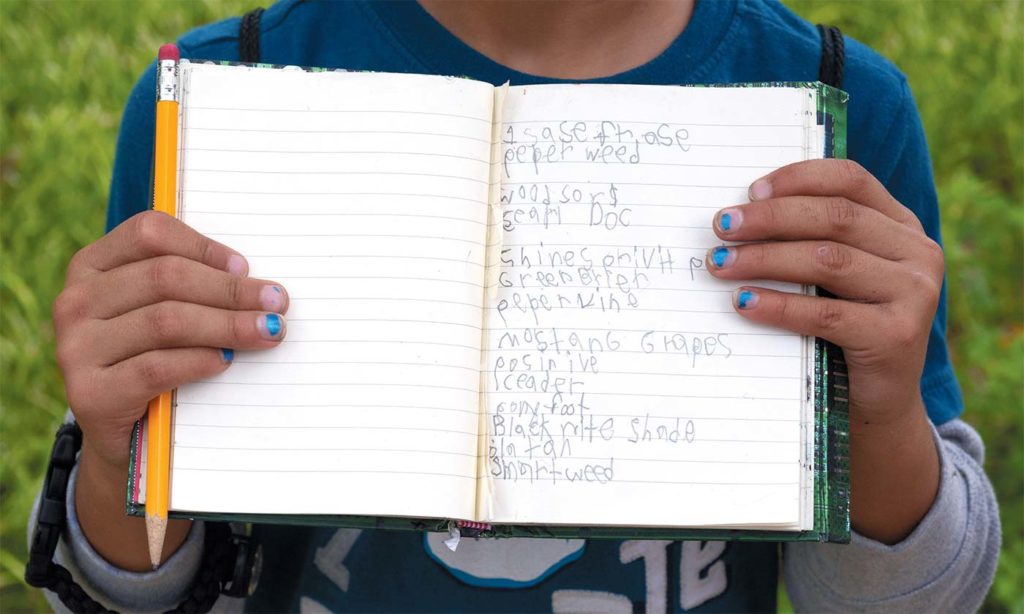

Sour-citrusy wood sorrel (left), Oxalis spp., often is mistaken for clover. But the two are unrelated. The Peña kids (center) show off their mustang grapes, or Vitis mustangensis. Tiny cucamelon fruit (right) is also called Melothria pendula.

Now as journeyman gastronome and seasoned chef at Goodfriend Beer Garden and Burger House, chef Peña’s passion for food has evolved.

“As my career moved along, I began to wonder more and more where the food we eat comes from. The food under our feet began to attract my attention more and more. It was a natural progression.” In addition to using wild onions and native pequin chiles in salsas, he also incorporates cactus pads (nopales) in tacos, and all sorts of wild greens into salads and garnishes. His proficiency for utilizing these foods professionally is extraordinary, but Peña’s more meaningful relationship with wild foods is at home during his down time.

A FAMILY FORAY

Peña elicits the help of his children Malia (11), Leia (10) and Kellan (7), making their foraging expeditions a family affair. Avid hikers and nature enthusiasts, the Peña family began noticing wild foods in their neighborhood, at parks and on camping trips with their scout group.

“Each time we go on a hike, my kids become more involved,” says Peña. “Everything from planning what supplies to bring, to which trail to hike. They are all scouts, which has helped teach them even more skills. As they get older, they become more confident—sometimes too much so—in the foraging process.”

The entire family takes foraging safety seriously, and each child can repeat the most important rule of foraging: “If you’re not 100% sure what it is, don’t eat it!” And their father is careful to oversee each step. “Even if I’m sure they know what it is, I still have them verify with me,” says Peña.

The chef employs other important measures that are critical for safe, fun foraging. “I carry a backpack with a med kit, bug spray, sunscreen, water and snacks. We discuss beforehand where we are going, what we may find, and what dangers to think about. The real point is to be as safe and prepared as you can each time you go out, even if it’s walking down the sidewalk in your neighborhood.”

Foraging with friends and loved ones can yield more than wild fruits and vegetables.

“It puts us in a position where we are learning together,” says Peña. “That quality time together is hard to find as a chef, and if we can do it outside in nature, instead of in front of a TV, that means the world to me. They are growing up appreciating the complexity of the world around us, and how we fit into it.”

THE MOST IMPORTANT RULE: BE SAFE!

While it cannot be reiterated enough, you should never EVER eat anything that you cannot 100% positively identify. True at any restaurant buffet, but even more important in nature. Many wild plants growing in our lawns, landscapes and wild areas are toxic. Some can even be deadly. Always refer to the botanical name when identifying a plant, and if you aren’t 100% sure, avoid it.

Remember the acronym I.T.E.M.

Identification: Never EVER eat anything that you cannot 100%, positively identify.

Timing: Many plants are edible when ripe, but inedible at other stages. Make sure you eat wild foods at the right stage of ripeness.

Environment: Be aware of your surroundings, whether in natural areas or urban spots. If there is noticeable pollution, stagnant water or even a mass of poison ivy nearby, the risks of harvesting might outweigh the rewards.

Method of preparation: Preparing foods the right way ensures that they are safe to eat and that they are palatable. As with cultivated foods, make sure to prepare wild foods for safe and tasty dining.

LEARN MORE ABOUT FORAGING

Wild foods are all around us from spring into summer and fall and even persisting throughout winter. From the dandelions, wood sorrel and purslane in our lawns, to wild grapes, mulberries and native walnuts growing in abandoned lots, or the pennywort, elderberry and cactus fruits growing on their own in the wild creeks, prairies and rangeland surrounding the metroplex. There are delicious surprises around every corner, if you take the time to look, learn and explore.

For those who find the idea of foraging appealing, there are some great resources to help you get started. One that both chef Peña and I use frequently is the website ForagingTexas.com, which includes an extensive database of many wild foods found across Texas.

There are also free guided classes on urban foraging that help you gain first-hand experiences, offered through Texas A&M AgriLife’s Water University program taught all over the metroplex in conjunction with several city partners.

Daniel Cunningham, Horticulturist with Texas A&M AgriLife's Water University program. His primary focus is a holistic approach to landscaping and food production systems. Cunningham specializes in Texas native plants and trees, vegetable gardening, edible landscaping, rainwater harvesting and is passionate about utilizing landscapes as habitat for benecial wildlife. For more gardening advice om Daniel, tune in to NBC DFW (Channel 5) on Sunday mornings or ask @TxPlantGuy on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/