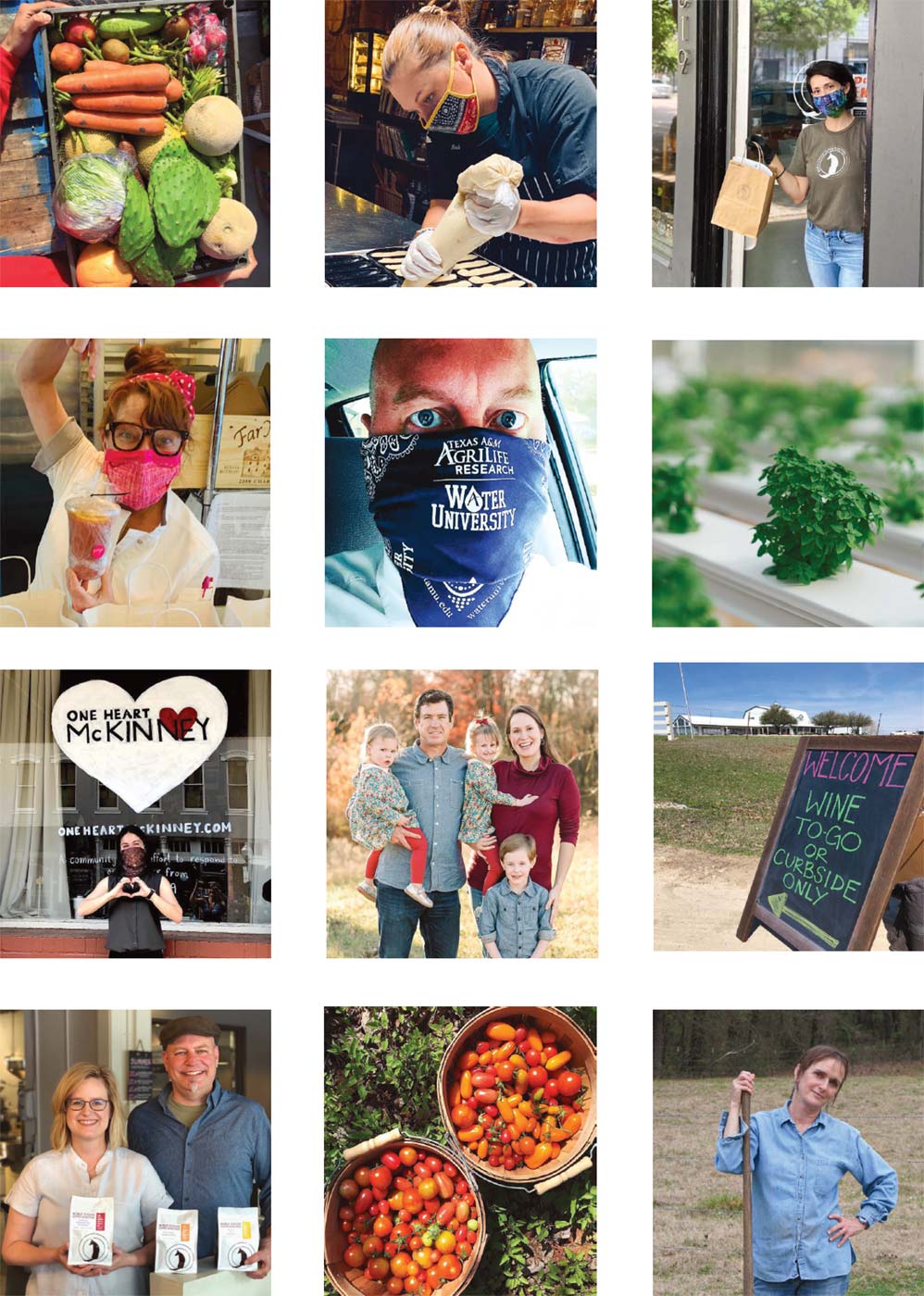

In a flash, COVID-19 turned the world on its axis and compelled us to rethink our lives. On the following pages, members of our food community, more linked than we ever knew, reflect on the pandemic from their unique perspectives as growers, food artisans, restaurateurs, food activists and journalists. Though the story is still being written, what have we already learned? About innovation and resilience, compassion and community? And where do we go from here?

EVE HILL-AGNUS

Dining Critic, D Magazine, Dallas

dmagazine.com

As soon as restaurants shuttered on March 16, my life shifted, but so did the lives of everyone in the industry. As the world of dining criticism went dark, I dove into telling the stories—first of crisis—that I saw around me.

The nimbleness and creativity astounded me, as restaurateurs and other food-related businesses, in a struggle for survival, reinvented themselves. Immediately, in the face of devastation that spread with ripple effects from those who grow the flowers that grace linen-clad tables to the farmers who grow the produce, the ranchers who raise the heirloom pork to the dishwashers who work long hours in the pit, I saw people spring into action. They formed a tight network. Even as they operated curbside pickup, their dining rooms empty, chefs helped farmers by saving the harvest through pickling, preserving and putting up. And meanwhile, farmers and ranchers donated to programs that kept furloughed or laid off industry workers nourished. Bread bakers championed local grain and led virtual seminars about foodways.

I saw people shopping locally, buying 100 percent locally produced dairy, meat, bread and produce. But also restaurants and individuals having the courage to try something new: meal kits, ghost kitchens sending out daring concepts and flavors. The plight of the hospitality industry, though, will remain foregrounded: the lack of safety nets for those who create and serve us. The curtain has been drawn back in a way that I hope will not recede.

DANAE GUTIERREZ

Executive Director/ Co-founder, Harvest Project Food Rescue, Dallas

harvestproject.co

Early in the pandemic, we were faced with two major dilemmas. The first was how to continue our distributions while maintaining the safety of our volunteers. The second was the growing number of those in need of food.

Thankfully, by following the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] guidelines, we did not have to stop operations. We also found out, though it’s a little bittersweet, that even through a pandemic food shortage there is still a lot of food available to rescue and deliver.

Our rescued food is surplus produce generously donated by wholesale produce distributors. We offer our baskets, without questions or requirements, to anyone who requests our help. Before COVID, we distributed baskets to about 600 families per week. That number rapidly climbed to 1,000 and it’s now at 2,500 families per week.

Almost everyone who receives our baskets contributes something— whether by volunteering or giving a quarter or a few dollars— to help sustain the program. With our new safety protocol, we quit accepting monetary donations at distribution sites and came up with the idea of Wholesome Wholesale online, where participants can purchase our affordable home delivery basket or buy a pay-it-forward basket for others.

When we were drowning in work, Dallas For Change provided us with additional volunteers and we’ve found more businesses willing to donate produce, which has made it possible to partner up with five new organizations and provide food for their families. One of the most amazing things that we have discovered about our community is that it is not determined by the location of where one lives but rather by the connections that we make with each other.

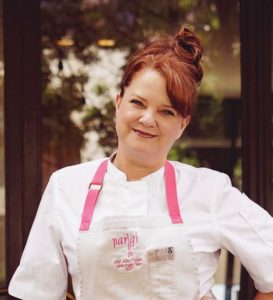

JANICE PROVOST

Executive Chef/Owner, Parigi, Dallas

parigidallas.com

The last night we were open— March 16—Parigi was packed for dinner. Our guests said if this was their last supper, they were going to have it at Parigi. I don’t think any of us thought that come August we would still be working through this. That first week is a blur. I know we brainstormed a million ideas. I put my head down in my “office”— formerly table 7. I didn’t want anyone to see the tears, but the team knew and showered me with love. We were going to stay in business—together.

Survival mode kicked in, and we focused on making the most of takeout and delivery. Because we have a strong catering background, we knew what food would transport well, and we wrote menus to reflect those offerings. Our customers were there to support us and that created much-needed momentum. Then something else incredible happened. We received The James Beard Foundation Grant. One of the most prestigious culinary organizations said, “We believe in you.” That was some serious affirmation. There was no way we were going to let them down.

My husband, Roger, and our accountant helped navigate the endless paperwork for the Paycheck Protection Program loan, and we were approved with our amazing partners at American National Bank. Also, our tight-knit Dallas chef community shared ideas and have been there for each other.

Who knows how things will shake out. I do know that I’m incredibly proud of our restaurant community, the resilience of our Parigi team, and the loyalty of our guests. We’re truly in this together, and we will do our very best to adapt and survive.

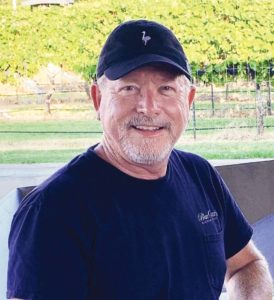

JOHN KILBURN

Co-owner, Comeback Creek Farm, Pittsburg

comebackcreek.com

We spend the winter months—December through February—planting and prepping. We always work hard during those slower months gearing up for the big spring and summer seasons when we offer our produce to restaurants and our Farm Box to home consumers.

Once COVID hit, interest in the Farm Box program— which we had already declared “full”—went way up. We could tell that our restaurant sales would be affected by the pandemic, so we determined we could accept more program members with what we already had planned and planted. We did our best to meet the demand and began advertising for our summer program one month earlier for people who were discovering us but couldn’t get in immediately.

Early on, it remained to be seen exactly how and for how long our primary channels for selling our vegetables—restaurants and Saint Michael’s Farmers Market— would be impacted. We responded first by making sure we were taking care of our Farm Box members and the chefs/restaurants who continued to order. Then, when we could tell we would have unspoken-for vegetables left to harvest, we made them available to the public via our email list and online ordering. The response was surprising and robust. Through these three channels— Farm Box members, chefs/restaurants and direct- to-consumer — we haven’t had to waste any of what we planted.

Cunningham by Eva Parks.

DANIEL CUNNINGHAM

Horticulturist, Texas A&M

AgriLife Water University, Dallas

wateruniversity.tamu.edu

I was somewhat ahead of the curve when my colleagues and I were advised to work from home. My job at AgriLife has always meant adapting to working from out-of-the-ordinary places— an old wooden chair in an unfamiliar public library, a dusty park bench, or, more often than not, my beat-up truck where I share office space with random plants and disheveled papers.

Change is always stressful, but others are dealing with far worse, and I feel blessed to still be working. We are all getting used to wearing numerous hats while trying to find the best way to balance homelife and work with only limited access to the family and friends who are our normal support network.

That means teaching folks how to grow plants—now live in a virtual setting—between diaper changes and the dogs barking at the delivery drivers. My wife and I tag team back-and-forth amid conference calls and online meetings. Now that we’ve found a routine (that is anything but ordinary), our work is streaming full speed ahead. As my new co-worker, my wife has actually helped me develop some online outreach logistics and goals (which balances out the fact that she might be the office loud-talker). Of course, I’m mostly kidding, but you learn new things about your spouse when y’all really see each other in the trenches of a work environment. (I love you, honey!)

PATRICK WHITEHEAD

Managing Partner/Winemaker, Blue Ostrich Winery & Vineyard, Saint Jo

President, Texas Wine and Grape Growers Association

blueostrich.net

The pandemic has certainly affirmed the sense of community we feel with our clientele. In reality, we have never referred to them as customers, they are our “guests,” and the lack of their presence at the height of the crisis has been felt, not only financially, but emotionally.

As an artisan winery, we aren’t a big player in the retail-shelf world. Our model is based on foot traffic and the chance to engage with the Texas wine consumer. We made the most of the few sales channels that remained not only during the initial shutdown, but also during the subsequent, and may I add unfair, shutdown of winery tasting rooms. We have instituted programs like curbside service, year-round shipping, online virtual tastings and even doorto- door delivery when it was practical.

Locals here in Cooke and Montague counties continue to purchase our wines and be our champions, but over half of our guests come to us from the greater Dallas and Fort Worth area. For many, a visit to Blue Ostrich is a chance to enjoy an hour of country solitude. They don’t just miss our wines—they miss the entire visceral experience. An outdoor patio and a glass of Texas wine is their happy place. It’s like going home. I know I speak for my fellow winery owners when I say that we look forward to welcoming back our guests and getting back to the business of educating and enlightening our valued community of Texas wine lovers.

SID GREER

Co-owner, The Greer Farm, Daingerfield

greerfarm.com

In March, we went from being totally booked in our cabins for spring break to almost no one wanting to come here. It went downhill from there until early May when folks decided they needed a safe place to get away. Our Facebook postings had been stressing that you could stay at our family farm and be socially distanced from others. Since then, we have been booked almost all the time. This has been a blessing.

Our blackberry and blueberry pick-your-own season was also a success. We required hand washing, social distancing in the field and a facemask for checkout, where we also had a plexiglas shield between us and customers. Customers were supportive of our rules and respected them.

Our Longview Farmers Market was delayed until June, but with strict safety rules, it has done well. We have been slammed with people wanting our all-natural lamb, pork, chicken, beef, eggs, honey and jams. We struggled to keep supplied and started delivering to Dallas customers which “saved our bacon” to some extent.

Everyone has been so supportive of our farm and has reached out to ask how we are doing. They have encouraged us. Our long-range plan is to continue to be more focused on delivery to Dallas and to continue to meet the needs of those wanting a safe farm stay.

MARTA SPRAGUE

Co-owner, Noble Coyote Coffee Roasters, Dallas

noblecoyotecoffee.com

When COVID hit, we closed our coffee shop and, as you can imagine, our wholesale orders from restaurants slowed considerably. Grocery stores picked up some of that slack, but what has been really amazing is the support from the community. Our online orders increased. Our emails from customers increased. We have felt so much love.

Only our roastery team is allowed inside now, but we have started our “Curbside Cafe” where people can pre-order drinks and bags of coffee online and swing by to pick them up. We’ve been so lucky that people have responded well to that. Our team practices social distancing, wears masks, performs daily temperature checks and sanitizes through the day. We will continue our monthly brewing classes online until it’s safe to resume at our roastery. We also do online cuppings (coffee’s version of a tasting). People order a sampler of coffees with setup instructions and then we discuss in a live online chat.

I’ve worked from home since March. My allergies/asthma put me a bit at risk, plus I’m alternating trips with my sisters to check on my elderly mother in Arkansas. I’ve basically been in lockdown handling the administrative work, and I shop through delivery services for groceries. Having a small business affected by this has made us search for ways to help others in the

Nick Burton.

JEFF BEDNAR

Farmer/Founder, Profound Foods, Lucas

profoundfoods.com

When our restaurant customers dropped from 130 to only four in just one week, we knew we had to pivot our business fast in order to stay afloat. As a food hub, Profound Foods represents not only our family farm but a network of 40 other local farmers and ranchers as well.

We surveyed our social media followers about launching to home consumers and when the response was positive, we put robust safety protocols in place and leaped into both home delivery and delivery to pick-up outposts. We pared down our 150 varieties of culinary herbs, microgreens and edible flowers, the ones we didn’t think home cooks would buy, and business has exploded. Profound Foods is now doing more than twice the weekly volume it did pre-COVID. It has been important to keep listening to our customers’ requests, which is why we launched The Profound Kitchen with Chef Nick Walker, who is creating value-added foods with the extra produce that would have gone to waste.

Our nation’s food supply chain, which has long been environmentally unsustainable and unfair to most farmers, was due for a big change, but we had no idea how quickly it would come. We hate to see the suffering, to see our service industry friends hurting financially and businesses crumbling under the stress of the pandemic. What we love, however, is seeing the renewed appreciation for locally grown, sustainably produced foods. We hope that the demand for safe foods keeps growing.

WENDY TAGGART

Co-owner, Burgundy Pasture Beef, Burgundy Boucherie, Grandview

and Burgundy’s Local, Dallas and Fort Worth

burgundypasturebeef.com

The pandemic has shed light on the need to bolster the infrastructure of small-scale meat processing. At Burgundy Pasture Beef, we have seen this from our unique perspective as not only producers of grass-fed beef, but also as custom meat processors and direct-to-consumer retailers.

When mainstream meatpackers hit a snag (outbreaks of COVID-19 at mega facilities), local small-scale processors and abattoirs did not have the capacity to pick up the slack. Word has it that smaller facilities in North Texas and beyond are months out from being able to schedule more animals, which creates an unfortunate bottleneck in giving local consumers access to the bounty of what North Texas has become—a great resource for sustainable meat.

The good news is that Burgundy Pasture Beef, along with others, is putting the pieces in place to answer the call. But it will take time and money. Small-scale systems can’t be all things to all people, but our food security shouldn’t completely depend on a handful of large meatpackers where efficiency often takes precedence over quality.

I have always believed that consumer demand is what brings about change, and in the 20 years since we started, the change has been profound. But the pandemic has reminded us that more is needed. If consumers continue to demand better quality and wholesomeness from their meats, then policy gurus will understand the importance of “local” and “small-scale” when creating a more secure food system.

RICK WELLS

Co-owner, Harvest Seasonal Kitchen and Rick’s Chophouse

Founder, The Seed Project Foundation, McKinney

harvesttx.com

spftx.org

rickschophouse.com

The feeling that struck me early on, and more than anything else during this crisis, was grace. It has come from every direction, reconnecting people all around us. It is unbelievable how gracious people have been. Gracious to each other and to our community mission. Those little things in the restaurant that can become a small crisis are now pushed aside with a smile. A missed reservation, the wrong temp on a steak, a sold-out item—people seem to be letting things roll off their backs just a bit more.

Early on, we talked about getting out of the wagon and pushing it up the hill together. We closed the restaurant on a Friday and by Sunday, our leadership team was feeding our staff who had been furloughed. When we reopened, staff members were working eight to ten shifts a week, and in hot kitchens, wearing masks nine hours a day without a complaint, doing anything and everything to save our company.

I’ve experienced a lot of the same personal disappointments that our guests have—cancelled events, missed graduations, postponed vacations—but through it all, I’ve witnessed the most unbelievable teamwork. My hope is that our community will continue to take care of each other as we emerge on the other side of this pandemic with more patience and understanding. I also hope that we continue to shop and eat a little closer to home as we rebuild our networks and that we proceed with grace as we get the hell out of 2020.

As a kid, TERRI TAYLOR refused to eat her vegetables. Her veggie-phobia was cured in 1977 when she spent eight months working on farms in Norway and France. She studied journalism at UT-Austin and received a master’s degree in liberal arts from SMU. Her short story “Virginia” can be found in Solamente en San Miguel, an anthology celebrating the magical Mexican town of San Miguel de Allende. She has written for Edible DFW since its inaugural issue in 2009. She became the magazine’s editor in 2010 and is the editor of Edible Dallas & Fort Worth: The Cookbook.

- Terri Taylor

- Terri Taylor

- Terri Taylor

- Terri Taylor

- Terri Taylor

- Terri Taylor

- Terri Taylor

- Terri Taylor