Baskets of kohlrabi (above, left) at Cold Springs Farm CSA

Baskets of kohlrabi (above, left) at Cold Springs Farm CSA

drop in February. Farmer Beverly Thomas

(above, right) with an armload of salsify.

The Weird and Wonderful Vegetables

of Farmer Beverly Thomas

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JESSI AND MATTHEW RAINWATER

Years ago, if you were a Southern farmer looking for commercial pesticides, Beverly Thomas was your go-to gal. Today, the former sales rep doesn’t go near the stuff; she’s an all-organic farmer. Her Cold Springs Farm north of Weatherford is in the final year of a three-year conversion to organic certification. “I have such a knowledge of pesticides that it makes the transition to organics easier for me,” she says, standing in the middle of a field. On this blustery winter day, she’s dressed in shorts and a neon-orange vest.

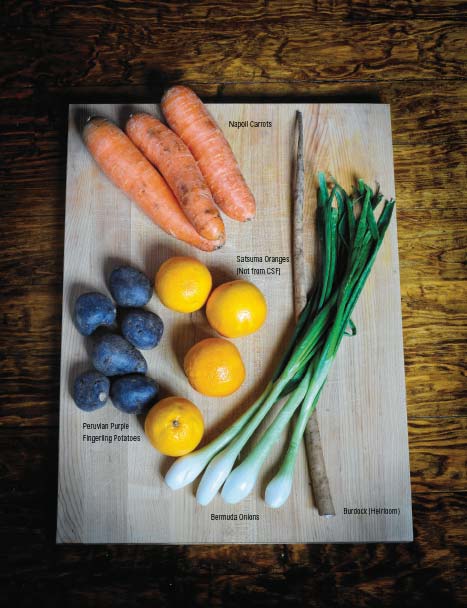

She grows rare and heirloom varieties of everything from lentils to melons on eight of her 35 acres. That includes artichokes. Cardoons. Bananas. Bananas? Yes, in a greenhouse. She grows root parsley, which people mistake for parsnips. Floppy Chinese celery. “I grow rare and heirloom melons that are commercially extinct,” she says. “I get the seeds through USDA. I grow over 150 varieties of melons and over 200 of watermelon. I’ve got 30 varieties of lentils. Last year, I grew about 150 tomato varieties.” She shares the remote spread with four horses, two fuzzy Bouvier des Flandres dogs, a Sebastopol goose and a bunch of chickens.

But you’re not going to find her root parsley and melons at farmers markets. What Beverly doesn’t distribute to her CSA members gets snatched up by chefs, including Dallas’ Stephan Pyles, Matt McCallister at CampO Modern Country Bistro and Grace’s Blaine Staniford in Fort Worth. It’s her fifth year for the CSA, or community supported agriculture; members purchase farm shares and get a portion of the harvest in return.

Baskets of artichokes (above, left) at Cold Springs Farm CSA

Baskets of artichokes (above, left) at Cold Springs Farm CSA

drop in February. Flossie (above, right) on the trail of feral hogs.

The kitchen staff at CampO relishes the arrival of her hulking, red Ram pickup, says McCallister. After she fulfills the CSA in Fort Worth, she takes anything left over to the chefs. “Her truck is full of awesome produce,” McCallister says. “I like the weirder vegetables, like she brought me burdock.” He wound up doing a classic pickled version of the Asian root. He drew attention to her farm before Christmas when he posted on Facebook that he had local artichokes on his menu. Anyone in the know knows artichokes don’t grow in Texas – except now they do.

“I love this woman,” says Hibiscus chef de cuisine Michael Williams. From the moment he met her at Fort Worth’s Cowtown Farmers Market in 2010, he was impressed with her passion and knowledge. “She was just as excited about food as I was,” he says. He remembers her insisting that he try her heirloom cherry tomatoes. He was chef de cuisine at Fort Worth’s Brownstone at the time. “They were amazing. They went on the menu pretty quickly.” Since then, they’ve become friends. He helped her with a recent feral hog invasion, and she brings him a cornucopia of the unusual things she grows. “She’s a good teacher,” says Williams. “She understands the farm and organics and how that helps the world.”

I’m visiting Beverly on a cloudy day before storms break. Driving up the sandy path to her house, bushes screech and scrape against the car. The farm isn’t much to look at – at least not until you know what’s there. She had cautioned me to wear boots even though she’s sockless and has on moccasins. “The copperheads,” she explains, “never really hibernated,” and she doesn’t want me to step on one of the poisonous snakes as we walk the fields. Over in one, gauzy white netting flutters ghostlike in the wind. “That was where my melons were,” she says, and where she’ll plant them again this season. “I’ve been working with a seed grower in Japan. The Japanese, they trellis everything. That keeps the melons off the ground, which solves several pest problems.”

In another field, tented plastic tunnels shelter rows of peas and green garlic. “The favas are finally blooming,” she says, her blond hair pulled back against the wind, which has shredded a larger plastic tunnel. Wind is as much a problem for farmers in this area as drought and heat. She plucks a bit of lovage for me to taste. “I don’t know what chefs use it for, but I like it in salads and in beans.” She shows me where a fresh incursion of feral pigs has torn up irrigation lines and rooted through the plastic covering her carrots and other new plantings. Chef Williams has helped her trap and kill two of the destructive creatures; he butchered them and shared the meat with friends. In the bed of her truck, she has about $400 worth of seed potatoes – a dozen varieties from French La Ratte to Irish Cobbler. “There are cheaper varieties,” she says. “But it’s more fun to grow weird things.” That extends to the artichokes poking up on the terraced back fields, where she also has yucca and plans for figs. She shows me where the soil changes to high alkaline, with more caliche. “The thing that really likes caliche soil? Truffles.” People have suggested she plant peaches. “That’s $20 a pound vs. $1,800 a pound.” She looks at me as if to say, “Do the math,” and points through a gate: “That’s where the truffles are going to go.”

You could dismiss these as the rantings of a woman who’s spent too much time under the Texas sun, but to do so would be to miss who Beverly is. This farmer has a master’s degree in weed science and plant pathology from Mississippi State University and is only a few hours short of a doctorate. For years, she made her living researching pesticides and their effects on row crops. She blends scientific acumen with a Mississippi farming heritage. “I’m not against the use of pesticides,” she clarifies. “I’m against the misuse of pesticides.” Part of her career was teaching their safe application and, she reiterates later over lunch at Weatherford’s locavore-driven Fire Oak Grill, that she still would help any farmer with pesticide questions. But her personal analysis leads her to embrace organics. One of the reasons is soil health. “A healthy, living soil will have all kinds of healthy, living organisms. When your soil is good, your crop is better. It tastes better, and your plants are more bug-resistant. You can’t use herbicides and expect to have beautiful soil.” She adds an aside: Those insecticides (pesticides include herbicides and pesticides) that man tinkers with in the laboratory are derived from naturally occurring, organic pesticides.

Neither farming nor career brought her to Texas. Thank cutting horses for that. “I was riding cutting horses at the time,” she says. When she moved in 1992 from Memphis, Weatherford was becoming the cutting horse capital that it is now. When she later found herself without a job, “I said, ‘What can I do? I can farm, and I’m good at that,’ and I had some leftover seeds from research farming.” Her curiosity about a particular butterbean led her to the Slow Food Ark of Taste, which recognizes and preserves endangered foods; today she grows several Ark varieties. The legume she remembered from childhood turned out to be a Florida Speckled Butterbean, which she now grows. But she really got hooked on offbeat, heirloom varieties, she says, while perusing old seed catalogs from the ‘30s and ‘40s. From her work on the job as a soybean breeder, she also knew about the Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN) at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and wanted to try her hand at melon and watermelon breeding. In return for acquiring seeds from the seed bank, “we [plant breeders outside of USDA] provide GRIN with more seed and information on our projects.”

Like other farmers in Texas, Beverly was hit hard last summer by the double whammy of heat and drought, compounded by that West Texas wind, and she is actively making changes to avoid getting thumped again. “We’ve got to start using [plant] varieties that can take the heat,” she says, one reason she’s working with the Japanese seed-grower. “I’m getting more Asian varieties because many of their varieties are better acclimated for heat.” She adds: “We know the water situation is not going to get better.” She has one well and is digging another. She uses gray water from her house to irrigate nearby. She plants cover crops to retard soil erosion, although that goes against traditional beliefs that they compete with the main crop. “The summer before last, I planted peanuts,” she says. “It kept my soil from blowing away, and I got another crop, too [the peanuts]. I planted buckwheat for the bees. Rye grass is great. It exerts allelopaths which keep weeds from germinating.” The time may be coming, she says, when Texas needs to look at spring, fall and even winter as its optimum growing seasons. She hopes not. “Texas, until it gets too hot, has the perfect weather for growing things.” But if the drought is a harbinger, she is ready. “If we have another summer this year like we did last year, a lot of farmers won’t be in business. “I’m going to be in business,” she declares firmly.

site: coldspringsfarmcsa.com

Shush (Navajo for “bear”) guards the CSA table

Shush (Navajo for “bear”) guards the CSA table

KIM PIERCE is a Dallas freelance writer and editor who’s covered farmers markets and the locavore scene for some 30 years, including continuing coverage at The Dallas Morning News. She came by this passion writing about food, health, nutrition and wine. She and her partner nurture a backyard garden (no chickens – yet) and support local producers and those who grow foods sustainably. Back in the day, she co-authored The Phytopia Cookbook and more recently helped a team of writers win a 2014 International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Award for The Oxford Encyclopedia for Food and Drink in America.

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/