By Diane Morgan

I was young when the back-to-the-earth natural foods movement of the 1960s started. When Frances Moore Lappe’s seminal book, Diet for a Small Planet, was published in 1971, I bought it and read it cover to cover. To my mother’s dismay, I declared myself a vegetarian who only ate fish—what is labeled a pescatarian today. It was a valiant effort that didn’t last once I went to college.

I look back on those beginnings and think about where we are today, thanks to victory gardens, community-supported agriculture (CSAs), a growing network of farmers’ markets, and ever-expanding national chains of natural foods stores. When the big box stores promote packaged and fresh organic products, you know the message has trickled down. And the push toward healthier eating continues with schoolyard gardens and with educational initiatives coming directly from the White House.

Are we finding our roots? Are we going back today, to generations not so long ago, when our grandparents and great-grandparents ate seasonally and shopped locally because that was their only option? They ate roots because they were cheap, stored well, and were nutritious. They pickled and preserved and planted backyard gardens out of necessity and economy.

I remember fondly the tomatoes my father grew and the sinus-clearing horseradish my grandfather uprooted from his garden in preparation for Passover. My maternal great grandmother “put up” pickles, canned beets, and turned summer fruit into preserves. The neat rows of filled and labeled glass canning jars lined her basement pantry. On a low shelf were the crocks of pickles covered with linen cloth. What I think of as the revival of back-to-basics home cooking is what our forebears did out of necessity. Bread was baked at home, soup stocks were made from a mishmash of vegetable scraps and bones simmered all day on a back burner, cabbage was fermented and turned into sauerkraut, leftovers were eaten, and nothing was wasted.

I love this sensibility, and believe root vegetables, more so than many other edible plants, reflect these earlier times of scarcity and economy. Without the threat of war in Europe, my great-grandparents on my paternal side emigrated from Munich, Germany in the 1850s, prior to the American Civil War. They found their roots in Savannah, Georgia. My maternal great-grandparents emigrated from Lithuania in the 1880s. Like most leaving Europe, they came to the land of promise and opportunity, living modestly as they built a better life. I know from my grandparents’ and parents’ love of family gatherings that their Jewish traditions and holiday foods thrived. Old world ingredients, cooking methods, and recipes were passed down.

These family stories of uncertainty, travel, and hardship from the Old World to the New World are not unlike the intriguing tales of a vegetable’s diaspora from its origins to scattered lands. It’s a lovely metaphor to consider.

Most root vegetables have curious lore and odd stories from antiquity. Stories range from how some roots were used medicinally as aphrodisiacs and to how others were used to treat scurvy. The carrot common in every supermarket today was originally purple in color, native to Afghanistan, and can be traced back three thousand years. However, upon arrival in Europe, its purple hue was not well accepted, and it wasn’t until it was hybridized in the Netherlands from its original purple color to orange that it found favor.

The Buddhists held lotus root sacred as a symbol of purity. It is native to tropical Asia, the Middle East, and Australia, and has been cultivated for more than two thousand years. By around 500 BC it was being grown in the Nile Valley for its exceptional beauty, though the poor found greater value in boiling, drying, and grinding the seeds and rhizomes for food. In China, evidence of its cultivation dates to the Han dynasty (207 BC–AD 220). In India, a golden lotus flower is said to have grown from the navel of the god Vishnu, and, in China and Japan, Buddha is oft en depicted either holding or seated on a lotus blossom.

An Old World vegetable popular in central Europe and the Netherlands, parsley root is just beginning to catch on in the United States, where it is most commonly found at farmers’ markets. It was grown and used in Germany in the sixteenth century and was introduced to England from the Netherlands in the eighteenth century, though it never really caught on with cooks there. In central Europe, parsley root was one of several vegetables and herbs known as Suppengruen, or “soup greens,” which were traditionally added to the water in which poultry or beef was boiled for use in a soup or stew. If you ask a grandmother of Jewish or central European descent for a list of the essential ingredients in chicken soup, she is likely to include parsley root—my maternal grandmother did!

These tales of families and foods are intriguing and deeply interwoven— not to be forgotten, and in many instances revived. That was my hope in writing my cookbook Roots.

Excerpted from Roots: The Definitive Compendium with more than 225 Recipes (Chronicle Books, 2012)

RECIPE

Carrot Ribbons with Sorrel Pesto and Crumbled Goat Cheese

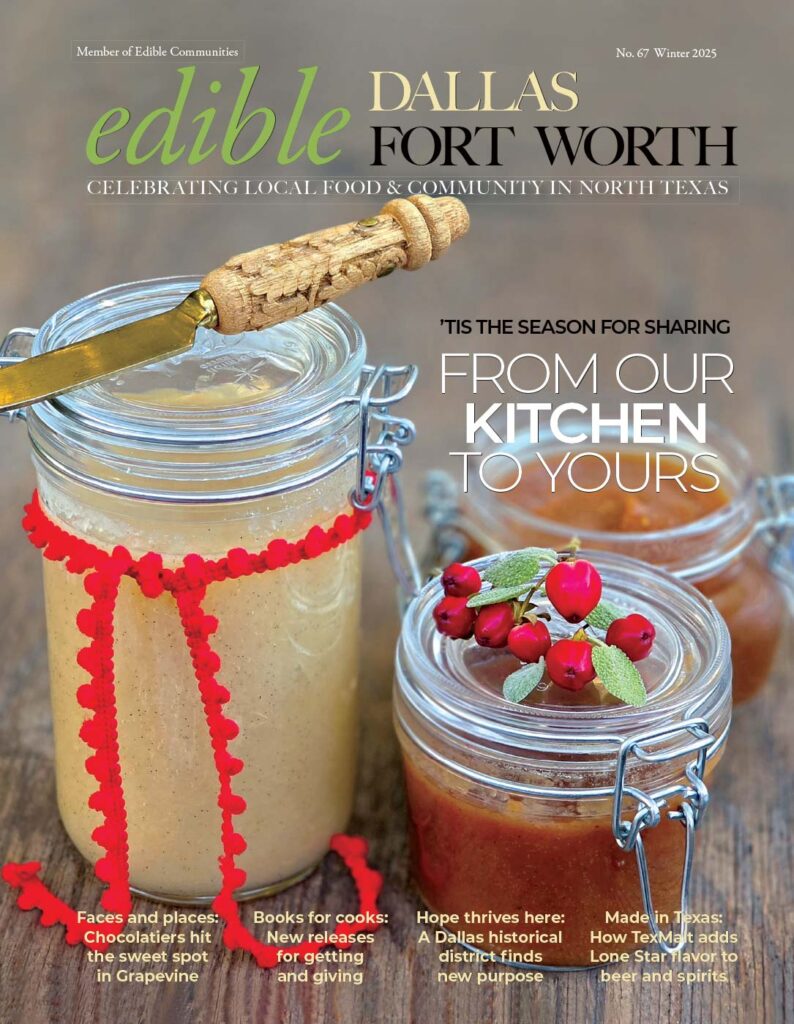

Edible Dallas & Fort Worth is a quarterly local foods magazine that promotes the abundance of local foods in Dallas, Fort Worth and 34 North Texas counties. We celebrate the family farmers, wine makers, food artisans, chefs and other food-related businesses for their dedication to using the highest quality, fresh, seasonal foods and ingredients.

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth

- Edible Dallas and Fort Worth