Hudspeth Farm

“We are just one family in one place,

determined to do what we can to

change our little part of the world.”

Photography by Kelsi Williamson

Dale Hudspeth is something of a cattle whisperer. His Angus cows race across the pasture to greet him, their thick, rich brown and black coats glistening in the sun. They huddle close to him, hopeful for a handout.

According to Dale’s wife, Linda, the cattle spook easily, but they are not afraid of Dale.

“He walks among them,” she says. Dale’s movements are smooth, deliberate and easy. He quietly studies the herd as they graze. They are healthy, well fed, and look—well—happy.

“They have one bad day,” says Dale, referring to their last. “Otherwise, they have a very good life. They are treated very, very well.”

He and Linda operate their business under the name Hudspeth Farm near Forestburg, a small community in Montague County.

They raise grass-fed beef and pastured pork and chickens in an environment as stress-free as possible to maintain the quality of the meat. They sell their products through several food co-ops and at farmers markets, and their meat is served at several North Texas restaurants, including Café 43 in the new George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, whose “local first, Texas second” menu features organic, seasonal dishes.

The Hudspeths are in the process of building a small store in front of their dairy barn to sell their farm-fresh beef, pork, chicken, eggs and raw milk.

“He’s always got an idea to do something,” Linda says with a glint in her eye. “When he says, ‘I’ve been thinking—’ ”

“She knows she’s in trouble!” Dale laughs as he finishes her sentence. Dale is a fourth-generation rancher and cattleman who tends to 1,000 acres that have been in his family since 1884.

“I got my first heifer when I was in the fifth grade,” Dale says. “My granddaddy gave me a bottle-baby calf, and I raised it up for a cow. She produced calves, and I usually bought school clothes and other necessary things with the proceeds. Later on I raised other calves, and I guess you could say that was my start in the cattle business. That was in the ’50s, so I guess you could say we’ve been in the cow business a long time.”

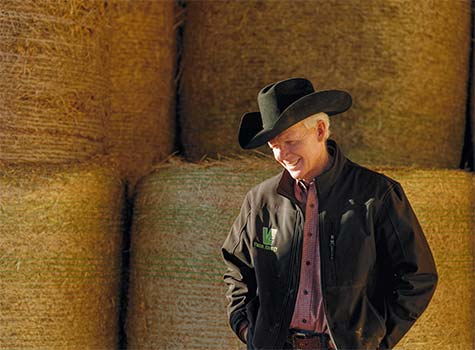

Dale Hudspeth

Dale Hudspeth

Dale graduated with a bachelor’s degree in park administration from Texas Tech in 1969, and Linda earned her bachelor’s degree in science from Texas Tech in 1971. The two married in 1975 and put in a commercial dairy in the late ’70s.

They adopted their grass-fed methods for purely economic reasons. According to Dale, it was much more cost-effective than carrying the feed to the cows. They started dividing up the pastures, and then divided them up some more, allowing the grass to replenish itself. At any one time, they had 200 cows on a single acre. The more the cows fertilized the pasture, the healthier the grass grew.

“We didn’t know it then, but we were ‘mob grazing’ back then,” Dale says. “Now it has become a popular way to build soil fertility and organic matter.”

Dale and Linda also discovered that the better the quality of the grass, the less grain the cows consumed. The cows’ health improved. They lived longer, fertility increased, and they had less metabolic disorders.

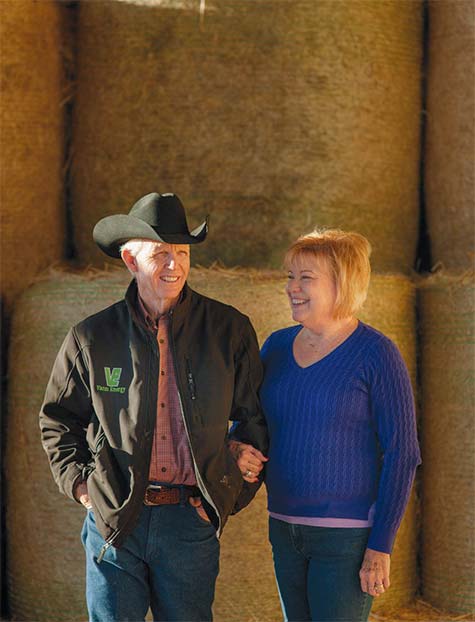

Dale and Linda Hudspeth

Dale and Linda Hudspeth

“Cows have four stomachs, and God designed them to eat grass and plenty of it. When you deviate from that, you have problems. We used to feed them like hogs, with a high-grain diet, and [they] suffered the consequences.”

Because of the intense workload and long hours, they sold the commercial dairy herd in 2001, after 24 years, and put their focus on meat production. “We were already set up to graze cattle on a quick rotational basis, so it was a no-brainer to set up a grass-fed operation. With 42 pastures complete with water, we began to run stockers,” says Dale, referring to the intermediate stage in cattle production when weight is put on weaned calves after which they are sold, prior to the final stage before processing. Eventually, Dale and Linda decided they could “finish” the cattle themselves on grass.

According to Dale, the pastures are covered in both common and coastal Bermuda grass. In the fall, the pastures are overseeded with rye and ryegrass as well as wheat, oats and clover. Sometimes radishes and turnips are also added to mix with hairy vetch. He finds that diversity is key. “We try to keep something growing year-round,” he says.

“We have a high-intensity grazing operation,” Dale says. “The cattle eat the grass all the way down, and they are forced to eat the whole pasture.” At this point, the cattle are moved to another pasture while the manure feeds the microbes in the soil that feed the plant. Once the grass has recovered, the cattle can return.

“We are in the process of soil development,” Dale says. “When you get the soil right, everything else falls in place. Healthy soils make healthy plants, which make healthy animals, which eat the plants, and then healthy people consume the meats. But it all starts with the soil.”

The chickens roam freely within screened-in huts and are moved to clean ground daily. They arrive as baby chicks, some with their shells still attached, and live out their days in fresh air. The pigs are also raised outdoors. “We want everything to have free access to pasture and green matter,” Dale says. “Chlorophyl is a real cleanser.”

In addition to the grass, the chicken and the pigs are each fed a custom mix without GMOs, soy or corn, especially formulated for their dietary needs. Hudspeth Farm’s practices are “beyond organic,” meaning that their methods go beyond the minimum legal standards to be certified organic.

Linda making deliveries

Linda making deliveries

Dale in milking barn

Dale in milking barn

the Jessups—Jansci, Sebron, Grace and Laughter

the Jessups—Jansci, Sebron, Grace and Laughter

Mondays and Fridays are delivery days, when Linda loads up her truck with coolers packed with meat and drives all over North Texas, making stops at the various vendors who carry Hudspeth Farm products. Linda retired in 2010 from a 34-year teaching career, which is also the year the grass-fed beef business took off.

While she handles the sales and orders, Dale tends to the ranch needs with help from a young couple, Sebron and Grace Jessup, whom the Hudspeths met through the Montague County Cowboy Church. It was perfect timing: The Jessups needed the work, and the Hudspeths needed the help. Though the Hudspeth’s three children grew up on the farm and appreciate it, they have chosen other careers and are not currently a part of the farm operation.

The Jessups have been on board at Hudspeth Farm for more than a year and a half and will help run the store and operate a raw milk dairy, the most recent addition to the farm. “We have the land and the facilities, and Dale has the knowledge,” Linda says. “And people need access to good, clean milk.” Their goal is to produce the bestquality milk from Jersey cows rich in beta-casein protein, which is more easily digested.

“We are what we eat,” Dale says. “I really believe that.”

“I think the food we eat or don’t eat is the key,” he says. “Certainly nutrient density plays a big part. Organic foods are proven to be more nutrient dense. GMOs are a big deal, and they are going to get bigger when folks find out the detrimental effects of them. Food – healthy, clean food free of artificial contaminants, is one place where we can have a say so. We are just one family in one place, determined to do what we can to change our little part of the world.”

ELLEN RITSCHER SACKETT loves to combine two of her passions, writing and food, and loves promoting other people's pursuits, which she accomplished as a writer/producer for the WFAA-TV show, Good Morning Texas, and as executive editor for Dallas and Houston Hotel Magazines. She occasionally contributes to The Dallas Morning News and was on the staff of its weekly entertainment magazine and digital team, dallasnews.com. In her spare time, Sackett cares for her many four-legged, furry and feathered family members and saves shelter dogs through Little Dog Rescue, which she founded. She invites you to follow her on Facebook.

- Ellen Ritscher Sacketthttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/esackett/

- Ellen Ritscher Sacketthttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/esackett/

- Ellen Ritscher Sacketthttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/esackett/

- Ellen Ritscher Sacketthttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/esackett/