In their production facility—Michael McClendon, winemaker, and Marnelle Durrett, proprietor, of Kiepersol, a 63-acre vineyard and estate winery near Tyler. Photo: Terri Taylor

Young Turks were members of a political movement of students and young enthusiasts in the early 20th century working toward democracy in Turkey. They were willing to break with the past to create their vision of their political future. In the Texas wine industry, changes are afoot, largely driven by an equally young movement of educated, experienced and passionate partisans with their own vision of the future.

These “Young Turks of Texas Wine” are unapologetic about being unconventional and understand the risk of failure. Yet, they are undeterred on their quest for quality wines with a true Texas character, not just a rehash of the wines of other wine-producing states or even the wines of the ’70s and ’80s that gave birth to our modern wine industry.

Outside of Tyler, Michael McClendon, a young, degreed biology major, took a winemaking internship at Kiepersol’s 63-acre vineyard and estate winery and discovered his career path. “I entered the Texas wine industry and immediately started harvest and crush, worked long hours, and learned as much as I could,” McClendon says. “I was driven by my appreciation for the winemaking legacy here.”

The Kiepersol legacy began with founder Pierre de Wet, who proved many in the industry wrong by showing that he was a good enough farmer to establish a Bordeaux-centric winery in East Texas. The legacy continues with his daughter Marnelle Durrett, who took the reins upon her father’s death in 2016.

McClendon possesses that same can-do spirit and East Texas pride. “I particularly want to build greater awareness of this region—its wine quality and reputation,” he says. “While working with Bordeaux varieties and Syrah, I’m also excited by what Albariño and Mediterranean grapes might achieve in our area. I’ve already started helping other wineries around us optimize their vineyard and wine production.”

In Celina, north of Dallas, Chris Hornbaker started early, influenced by his family’s love for growing things. His mother, Linda, whom he calls “a California girl,” is a master gardener; his dad, Clark, is a farm boy from Kansas. Before going off to Grayson College to study winemaking, Chris helped plant the family’s Collin County vineyard. “We initially chose hybrid grapes (Cynthiana and Blanc Du Bois). But, then we tapped into the longtime North Texas winemaking legend Bobby Smith and got a recommendation for Tempranillo.”

Says Hornbaker, “I’m planting grapes in our estate vineyard and searching vineyards around the state with the goal of our wines being 100% Texas. We’re having good results with reds like Montepulciano and Aglianico and whites like Roussanne and Marsanne, and we’ve found the latter two varieties make seriously good sparkling wines, too.” When Hornbaker talks of 100% Texas grapes, he means not backfilled with non-Texas grapes, a practice at some Texas wineries.

Increasing in-state grape production is a common goal among these young compatriots, who strive to eliminate the use of out-of-state wine grapes. They’re exploring different varieties: reds include Tempranillo, Grenache, Cinsault, Syrah, Montepulciano, Aglianico and Tannat, and whites are Viognier, Roussanne and Vermentino. These may be unusual-sounding names, but these grapes from Europe’s warmer regions better handle the hot and variable Texas weather and consistently produce high-quality wine.

Andrew Sides, manager at Lost Draw Cellars in central Fredericksburg, grew up working the family farm in Brownfield with his mother, father, granddad and uncle Andy Timmons. “By the time I was in college,” says Sides, “I was tending Andy’s vines at Lost Draw Vineyards, whose plantings were expanding to meet the demand for Texas grapes.”

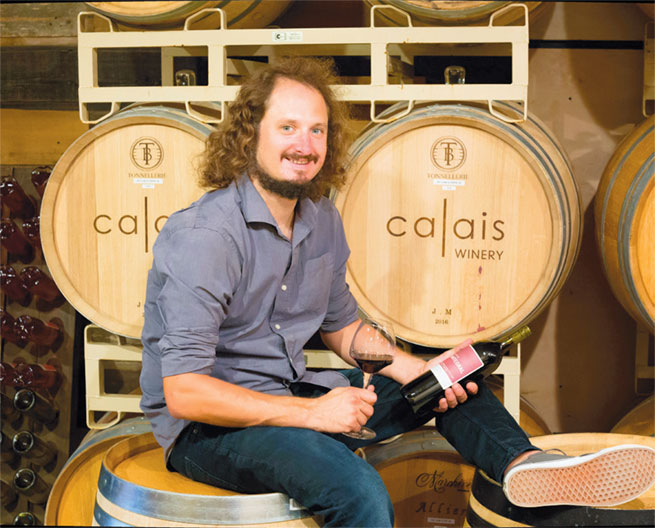

Later, he linked up with young winemakers who were buying his grapes. “We all had a similar perspective; this gave me the incentive to open Lost Draw Cellars,” says Sides. These Young Turks with wineries between Johnson City and Hye include Chris Brundrett at William Chris Vineyards, Doug Lewis and Duncan McNabb at Lewis Wines, and Ben Calais at Calais Winery.

Photo: James Skogsber

“We all had a similar perspective; this gave me the incentive to open Lost Draw Cellars.” —Andrew Sides

Photo: Clark Hornbaker

“My job as a winemaker is a perfect fit for me.” —Chris Hornbaker

Brundrett founded William Chris Vineyards with longtime grape grower Bill Blackmon. “Our passion was to figure out what the different regions of Texas actually ‘taste’ like,” says Brundrett. “We wanted to explore real Texas wines that speak about where they were grown—their terroir.” At William Chris, they make 100% Texas a tenet of their business plan and, with others of the same ilk, are seeking support in Austin for what, in time, will produce laws supporting 100% Texas grapes in Texas wine.

Lewis and McNabb came together when interning for winemaker David Kuhlken at Pedernales Cellars in Stonewall. Small plans to make just enough wine for family and friends took a turn after sharing some of it with Brundrett. According to Lewis, “Chris told us it was good and that we should start a ‘real’ winery, that’s now Lewis Wines.”

Their goal is what McNabb calls “making high-quality Texas wines over a range of prices in ‘value’ to ‘premium’ categories.” To do this, rather than focus on particular grapes, Lewis and McNabb try to stay flexible, looking across the state for their line of dry, minerally rosés, dry whites made from Chenin Blanc and Viognier, and a light semi-sparkling blend made with Texas hybrid Blanc Du Bois grapes.

Photo: James Skogsberg

“I’m going for specific vineyards with elevation (higher than 3,000 feet).” —Ben Calais

A native of France, Calais brought his Calais Winery to the Hill Country from Dallas after working several harvests at French wineries. With his Texas winery now in its tenth season, Calais is gaining focus. “I see my future in combining Bordeaux varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Malbec and Cab Franc with heavy hitters like Petite Sirah and Tannat,” he says. “In addition, I’m going for specific vineyards with elevation (higher than 3,000 feet), like around Fort Davis and the Texas High Plains, where Bordeaux varieties have shown they can make world-class wines.”

Photo: James Skogsberg

“While style may only be 10% of the winemaking process, I feel it’s the most important 10%.” —Brock Estes

Industry insiders will recognize a familiar name south of Fredericksburg— Newsom Vineyards—followed by “in Comfort.” In 2016, Nolan Newsom and his wife Yanmei took a risk and opened a Hill Country tasting room. (Nolan is the son of High Plains grower Neal Newsom, who’s been planting vineyards since 1986.) Says Nolan, “For decades, our family has grown grapes and sold them to wineries to make wine, selling under their labels. We’ve reversed things up. In our tasting room, we are selling wine from our grapes, made by some of our favorite winemakers, and sold under our Newsom and Inception labels.” Their hope, adds Yanmei, is to extend the Newsom Vineyards legacy.

Just a short hop away, there’s Brock Estes. His family goes back six generations in Mason County, where he has two passion-filled wine ventures going. “My Dank Wines project is a brand of easy drinking blends aimed at millennials,” says Estes. “But with Fly Gap, I’m operating on a shoestring budget and a little on the fringe. I can take time to explore my wine style with Fly Gap. To me, while style may only be 10% of the winemaking process, I feel it’s the most important 10%.” Estes’ approach is to extract in his wine as much from the land and its terroir as possible, even in fermentation.

Photo: Nivien Saleh

“It was time to find a job. While I was drawn to California, my heart was in Texas.” —Tiffany Farrell

On the coast in Galveston County, Tiffany Farrell is the winemaker at Haak Vineyards. A Texas A&M graduate in microbiology, she later found her future in winemaking by working harvests at Napa’s historic Weibel Family Vineyards and Justin Winery in Paso Robles. After graduate school at Boise State and some experience in Idaho’s Snake River wine region, she recalls, “It was time to find a job. While I was drawn to California, my heart was in Texas. When I saw Raymond Haak’s posting on winejobs.com, I said, I want that job!”

Having just started at Haak, Farrell admits to being a little overwhelmed. “The geography of the Texas wine industry is impressive. For example, take the 600-mile trek grapes make from High Plains vineyards to our crush pad in Santa Fe.” She also acknowledges the diversity of grape varieties that grow here is challenging for a winemaker. “I’m blown away with the Texas wines I’ve tasted and eventually want my Texas wines to be recognized from coast to coast, especially when I go out to visit my friends and colleagues in California.”

Young Turk gathering at William Chris Vineyards in Hye. (left to right): Chris Brundrett, Ben Calais, Andrew Sides, Doug Lewis, Duncan McNabb, Rae Wilson. PHOTO: JAMES SKOGSBERG

Winemaker, marketing professional and certified sommelier Rae Wilson came to Austin after garnering experience in California. She founded Wine for the People and offers consulting services for wineries in need of market strategies. She feels that a lot of wineries make too many wines and spend too much time apologizing for what Texas isn’t rather than embracing what it is. Her creative spark is finding wine styles that make sense from both grower and consumer perspectives.

She has launched her own brand, Dandy Rosé, a dry French-style rosé. “I wanted to show Texas winemakers that a wine like this is the perfect entry point into the marketplace,” says Wilson. “Rosés are simple, but you can fuss over them if you want. ey are a perfect t for the climate and lifestyle in Texas, and they can be made from a range of red grape varieties that grow well here.”

These Young Turks are representative of many who are now searching for the high-quality Texas wines of tomorrow. With youthful grit and fearless determination, they’re making an impact, and with the likelihood of having 30 vintages in front of them, they have time enough to craft the future.

- Russ Kanehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/rkane/

- Russ Kanehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/rkane/