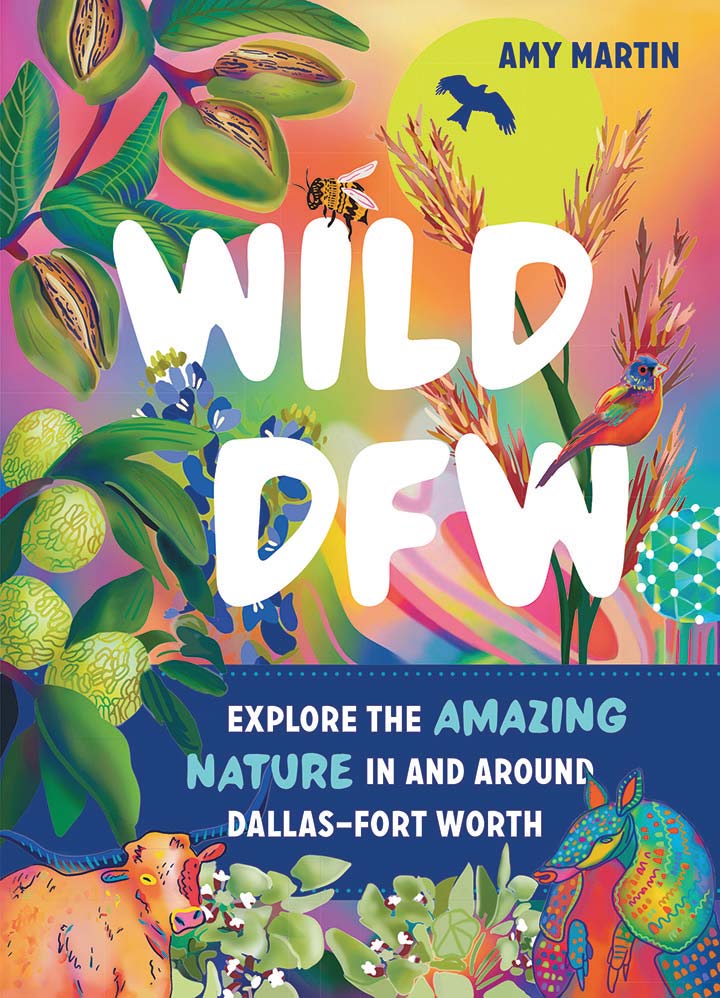

Amy Martin ventures beyond the concrete jungles of North Texas in her new book that appeals to young and old

In her book Wild DFW: Explore the Amazing Nature In and Around Dallas–Fort Worth (2023), Amy Martin shares the marvelous poetry of being in nature. A fabulously sensitive guide, she reiterates mottos for life, which anyone who ventures outdoors will recognize: Slow down and experience with your senses. Martin was approached by Timber Press about this volume in their Wild series, which includes cities such as LA, Miami and Philadelphia. Her own journey had taken a wild turn only months before. Martin had broken her neck—a serious injury that confined her for months to looking out her window and immersing herself in Google Map satellite-view reperage of “all the nature places.” She vowed to return to or discover them all. “And it was my motivation to get better,” Martin says. As she learned to walk again, volunteers accompanied her on treks: first around the block, then farther afield, to increasingly challenging spots. Those hikes nourished the final third (the DIY “Adventures”) of the 370+page Wild DFW.

Within its chapters, Martin first introduces readers to the ecosystems in four North Texas counties: eight different types of soil, each with a distinct plant, insect and wildlife community. Then she empowers you to make your own discoveries. “We’re not a vista-driven landscape. We’re a very intimate landscape,” Martin says. “You have to immerse yourself in it and see it up close.” She encourages “hiking at the speed of botany”—about 1 mile per hour. Here we urge you to plunge into some tips and an adventure. And pick up the book! —Eve Hill-Agnus

This excerpt from Wild DFW is courtesy of Timber Press. The book includes maps, photography, tips and history. For a list of retailers and more information, go to wilddallasfortworth.com. Amy Martin is also the author of Itchy Business (2016), a book about poison ivy and oak. moonlady.com; IG: @amymoonmartin

TRINITY RIVER AUDUBON CENTER

Trinity River Audubon Center (TRAC) is a sampler of North Texas ecosystems. Boardwalks skim over wetlands, chipped granite trails thread through prairies and upland woods, and dirt trails pad through riparian woods for five miles of paths. All securely contained in 130 acres with a modern educational center at its heart.

Jake Poinsett and Marcus Cole share their knowledge as Trinity River Audubon Center educators with me on this warm spring day. We take the boardwalk across the big Trailhead Pond. The shady Wetland Trail wanders among seasonal ponds, with small bridges spanning rivulets and side trips to bird blinds.

Wetlands Wonderland It’s a wet spring, so Cattail, Dragonfly, and Great Egret ponds ooze into one long bayou. In drier times they’ll be distinct ponds, at times very small. The topic quickly becomes about a beaver that Jake says “is doing his own wetland engineering.”

The beaver fells young black willows but leaves enough bark so the tree survives. “It makes its own food,” says Jake, noting that the rodent grazes young willow shoots emerging from the now reachable trunk. Marcus observes the beaver’s broad muddy path through reeds. I share that the salicylic acid in black willow bark soothes beaver incisors. With this nature nerd triple swap, we are now fully bonded.

Jake and Marcus hear birdsongs, raise binoculars, and identify birds one after another, training for the national Bird Bowl ahead. Thickets of roughleaf dogwood abound with short-lived umbels of white flowers that pop in the dim, dappled light. Birds will flock here in early fall for the white berries, eaten by over fifty species.

TRAC’s wetlands attract migrating waterfowl like coots, shovelers, and teals, and shorebirds like greater yellowlegs and the very loud ring-billed gull. Over a dozen sparrow species pass through, notably Harris’, LeConte’s, and savannah, along with towhees, warblers, and wrens. Migrating along with them are birds of prey like northern harrier and sharp-shinned hawk.

TOXIC DUMP TO ECO-TREASURE

Dwarf palmettos grow in an open glen, a homage to deep parts of the Great Trinity Forest (GTF) where they still grow in the wild. The trail swings into the Blackland Prairie restoration. Beyond TRAC fences sits a massive two-story slope dotted with landfill monitors, reminding that the area was once the largest illegal dump in Texas containing 1.5 million tons of industrial refuse.

Over two decades, the dump leaked toxic chemicals and caught fire twice, smothering an adjacent African- American neighborhood in black soot. Finally, a federal court case ordered restoration by the dump operators, who then abandoned the property. “It decimated the ecosystem far beyond here,” says Marcus. A $37 million environmental remediation led by the city of Dallas ensued.

Designers crafted a 130-acre swath of excavated land into TRAC’s wetlands, woods, and prairie. The 21,000-square-foot LEED-rated education center sits in its midst, radiating ecological stewardship with its recycled materials, vegetated roof, rainwater collection, and energy effciency—a fitting coda to an environmental crime. Where surface waters once ran in toxic neon colors, healthy waters now flow. Small-mouthed salamanders slither through damp leaf debris. Blanchard’s cricket, green tree, and southern leopard frogs cling to pondside plants. Green anoles skitter about nervously, hoping to find a meal without becoming one.

SAVANNAH KNOLL

Rising out of the wetland, we ascend a small knoll into a short motte of post oaks, Eve’s necklace, and Mexican plums. I remark about the red sandy soil. “It’s a finger of Post Oak Savannah,” says Jake. “Eco divisions aren’t as clear as maps make them.” We absorb the view of the wetland ponds, lush in a myriad of light spring green tones.

I imagine the wetlands gradually receding as hot weather evaporates the water, greenery diminishing to a wisp of its former self. Small fish, tadpoles, and crustaceans become stranded in the muck, providing a feast for shorebirds, barred owls, raccoons, and opossums, before summer thunderstorms fill them again.

As we depart the knoll, an Eve’s necklace grows out of the steep slope, placing opulent dangles of lavender flowers at face level that I inhale robustly. Native plant gardens separate the parking lot sections on our way back, providing seed for future prairie rehabilitation.

FOREST STROLL

Jake and Marcus go back to work, leaving me to stroll the forest trails. The well-shaded path starts wide and travels along two shallow ponds lost in the trees. Then the trail narrows, and a sense of the GTF emerges.

Scattered immense pecans stand like teachers among younger trees only a few decades old. The forest floor is a brilliant green sea of Virginia wildrye and broad-leaved forbs. As the path widens again, I come to TRAC’s most significant tree: a pecan twelve feet around and towering three stories tall. With over two centuries of life under its bark, it commands respect.

I depart the woods for the Great Blue Heron and Spider Web ponds, taking the forested backside trails for new views and more big trees. Cottonwoods flap their leaves noisily in the wind. Soon I’m at the Trinity River overlook, a rare chance to picnic right on the river and a fine place to rest before heading home.

TRINITY RIVER AUDUBON CENTER

Southeast Dallas, off Loop 12 between I-45 and US 175.

6500 S. Great Trinity Forest Way

Dallas, TX 75217

trinityriver.audubon.org

- Trails Soft surface 2.5 miles. Trail map at website.

- Facilities Visitor and educational center.

- Free entry through June 30, 2025 (thanks to an accessibility initiative). Reserve timed tickets. Dogs Not allowed except service animals.

BEFORE YOU GO

Apps exist that will tell you a land’s owner. “So when it’s city of Dallas property, I’ll see what’s out there,” looking for signs to make sure it’s open to the public. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers owns land around most reservoirs. Dallas County Open Space runs about 20 preserves that exist primarily to support wildlife.

Look and listen in layers. Open your mouth so you can breathe, smell and taste a space. —Amy Martin

Amy Martin is the author of Wild DFW from Timber Press. The book includes maps, photography, tips and history. For a list of retailers and more information, go to wilddallasfortworth.com. Amy Martin is also the author of Itchy Business (2016), a book about poison ivy and oak. moonlady.com; IG: @amymoonmartin PHOTO BY STALIN SM

-

This author does not have any more posts.

EVE HILL-AGNUS teaches English and journalism and is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She earned degrees in English and Education from Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Dallas Morning News, D Magazine, and the journal Food, Culture & Society. She remains a contributing Food & Wine columnist for the Los Altos Town Crier, the Bay-Area newspaper where she stumbled into journalism by writing food articles during grad school. Her French-American background and childhood spent in France fuel her enduring love for French food and its history. She is also obsessed with goats and cheese.

-

Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

-

Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

-

Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

-

Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/