The farm-to-table movement has (re) connected folks with local farmlands and backyard gardens. The renewed appreciation for fresh-picked, sustainably-raised food has led to a refreshing new awareness—an environmental revolution of sorts. How do we protect our precious resources—water and land—AND better manage the food we grow?

A sad truth—up to 40 percent of the food produced in the United States is wasted. That’s one pound per person per day. A waste of both our farmers’ hard labor and our country’s natural resources.

And it’s not just about being green. It’s also about saving “blue.” According to the Food Policy Research Center, uneaten food in the U.S. annually accounts for 25 percent of all freshwater consumption.

The Environmental Protection Agency reports that only 5 percent of food waste gets composted, which means 95 percent doesn’t. In fact, the EPA shows that unused food, after paper and cardboard, is one of the largest constituents of municipal waste. In the city of Dallas, 30 percent of what goes to the landfill is kitchen and yard waste, things we could and should be composting. I don’t mean to talk trash, but I’m confident we can do better.

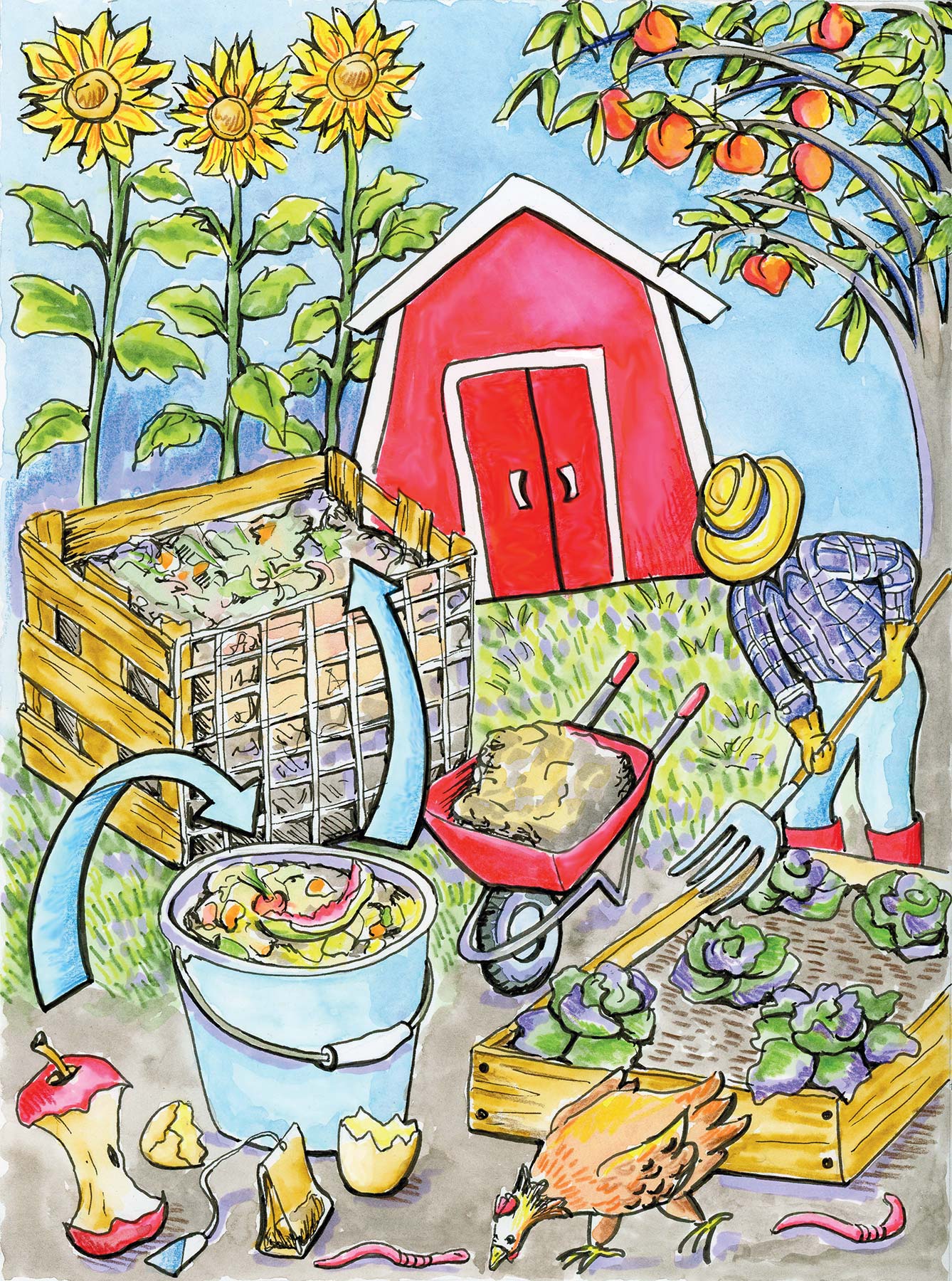

The problem must be tackled on many fronts (utilizing scraps in our recipes, freezing or canning produce before it spoils), but when spoilage happens, the most environmentally and economically friendly solution is to compost. Let’s call it “table to farm.” Or maybe in your case, “table to garden.”

Getting Back to Our Roots

Composting—the process of converting organic waste into a nutrient-rich soil amendment—is the best way to recycle uneaten or spoiled food. This age-old practice is mentioned in the Talmud, the Old Testament, in ancient Chinese writings and Hindu texts and was practiced by the Greeks and Romans.

It was also instrumental early in America’s history. Founding Fathers Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and John Adams, all avid gardeners, were intrigued with the practice of composting to improve soil health. George Washington, a dedicated compost aficionado, experimented obsessively with formulas, wading through byproducts from his fields, barns and house to improve production in his gardens, orchard and fields.

Today’s gardeners also see the value in combining kitchen scraps—vegetable peels, spoiled fruits, egg shells—with leaves or grass clippings to make compost. When combined in proper ratios and turned with a little water, “waste” can be transformed into the best soil conditioner for your farm or garden—all by using things we might normally toss in the trash.

Your plants will love you! Top dress established gardens with a ½-inch layer of finished compost or incorporate up to 3 inches of compost into the top 6 inches of unplanted beds. A bonus: Compost will help infiltrate water when it rains or when you irrigate, working like a sponge to retain moisture for thirsty plants during the hot, dry summer months.

Dig the Idea? Here’s How to Get Started

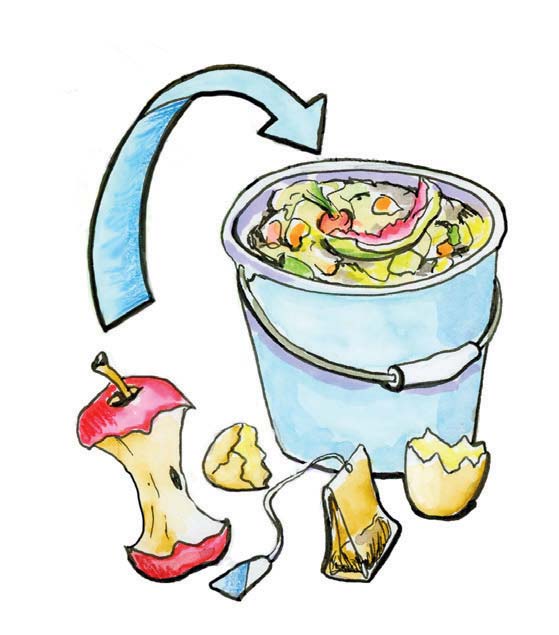

The practice of composting begins in the kitchen. To break the habit of trashing unused food, keep a small compost bucket or crock handy on the counter. (See sidebar on Page 12 for compostable items.) When full, waste can be transferred to your larger bin or pile.

The composting method you choose will depend on your needs. How much space do you have—a yard, an apartment balcony or a closet? How much waste does your family produce? How much compost do you need, and how much work do you want to devote to the task?

Composting skills take time to perfect, but it’s easy once you get the hang of it. There are piles of books, online articles and classes to guide you. The following is a brief outline to acquaint you with the basics, because a rind is a terrible thing to waste.

Conventional Open-Air Composting

An outdoor pile layered with leaves and food scraps is the most conventional method of composting. It can be hidden behind fencing or enclosed in a simple wire bin. Or you might invest in a rotating tumbler or commercially-made bin, depending on your budget and specific needs.

The process of decomposition takes a matter of weeks or up to a year, depending on whether you choose hot composting (the fastest, most labor-intensive method) or cold (the slowest, requiring the least work). Both follow essentially the same set-up with a few differences.

The S.M.A.R.T. Rules of Conventional Composting

Size: A compost pile should be at least 3 feet wide and 3 feet tall in order to provide enough room and insulation for beneficial microorganisms to thrive.

Moisture: Water must be added evenly between layers as you build your pile. The pile should stay as moist as a damp sponge. Any wetter and it will become stinky.

Aeration: If you are practicing “hot” composting, your pile should be aerated (turned) regularly (every two to four days when active) to allow the flow of much needed oxygen. is also redistributes beneficial bacteria, fungi and other organisms, and helps maintain your pile’s moisture and carbon/nitrogen ratios. In most cases, the more you turn your pile, the quicker you’ll achieve finished compost.

“Cold” piles are not aerated, which eliminates a lot of hard work. On the downside, a cold pile may take a year (or more) to decompose into finished compost. Heat is also necessary to kill off weed seeds, pests and plant diseases so it’s not advisable to add questionable plants to a cold pile.

Ratios: The goal is to create a well-balanced mix. Like the perfect lasagna recipe, you’ll need to layer ingredients in the proper ratios. A good rule of thumb is to layer (by volume) two parts of “brown” material (higher in carbon) to one part “green” material (higher in nitrogen).

Browns (not necessarily distinguished by their color) include dry leaves, wood chips, paper and saw dust. Greens often come from plants that contain moisture like fruit and vegetable scraps or green grass clippings. Coffee grounds are also an excellent source of nitrogen in spite of their color. Too much of either carbon or nitrogen can hinder the decomposing process.

Temperature: A compost thermometer will help you accurately monitor the heat in your pile. In a “hot” compost pile, a good carbon/nitrogen ratio will help maintain the optimal temperature of between 135°F and 165°F. Heat created by the respiration of organisms is necessary to break down organic matter. Temperatures higher than 165°F could begin to kill off those decomposers and inhibit the process.

In a “cold” compost pile, temperatures are left to nature, and the process occurs much more slowly.

Other Methods You Might Find aPEELing

Vermicomposting uses specialized red wiggler worms to break down organic material. The worms live in a small flat bin and when properly managed, this method produces the best quality compost. The worms need to be kept healthy. Conditions in their bin should be damp but not wet, and they don’t like temperatures below 50°F or above 85°F. For that reason, this is usually an indoor operation, especially in Texas. (Mine are in my garage closet.) There are a variety of online resources for supplies and information, including Texas Worm Ranch, owned by local worm wrangler Heather Rinaldi. Rinaldi and her crew frequently o er seminars at the company’s headquarters in Garland.

Bokashi is a two-step process that originated in Japan, mimicking an age-old Korean technique. The method doesn’t require turning and is great for those living in small spaces. The first step is more like fermenting food scraps, aided by the addition of a specially formulated bokashi bran. The second step requires burying your fermented scraps outside and covering them with dirt. Bonus: Some meat and dairy, forbidden in other composting methods, are okay when using this technique. Step one is best done inside at room temperature and requires draining the tea-like liquid off every few days. If you are in an apartment, finding a place to bury your compost can be a challenge.

Compost Services—Some DFW municipalities are considering following Austin’s lead and offering compostable waste pick-ups as a city service, but until that’s a reality, there are businesses to answer the need. Turn Compost and Compost Haste o er weekly pickups of kitchen scraps and yard waste for residences and businesses (in specific zip codes) for a reasonable monthly fee.

The finished compost can be returned to you or donated to a local neighborhood garden. Recycle Revolution, whose clients include the Joule Hotel and the Fairmont Dallas, recycles kitchen waste of all sorts from eco-minded businesses.

What Can Be Composted?

Fruit and veggie scraps

Egg shells

Bread, grains, pasta, crackers

Coffee grounds, tea bags

Beans, nuts, seeds

Leaves

Straw

Wood chips or sawdust (the wood must be untreated)

Yard trimmings

Shredded paper, cardboard and newspaper

What should not go in the

compost pile?

Meat, fish and poultry (small amount in Bokashi)

Dairy products (small amount in Bokashi)

Grease or oils

Pet feces

Treated wood

Ashes

Glossy paper

Glass, metal or plastic

Daniel Cunningham, Horticulturist with Texas A&M AgriLife's Water University program. His primary focus is a holistic approach to landscaping and food production systems. Cunningham specializes in Texas native plants and trees, vegetable gardening, edible landscaping, rainwater harvesting and is passionate about utilizing landscapes as habitat for benecial wildlife. For more gardening advice om Daniel, tune in to NBC DFW (Channel 5) on Sunday mornings or ask @TxPlantGuy on Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/

- Daniel Cunninghamhttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/dcunningham/