photo by Kalyn Hodges

photo by Kalyn Hodges

My first taste came in the form of the meatballs at Eno’s Pizza in the Bishop Arts District: savory, dripping and juicy, they made me reach for more napkins. My second was at Small Brewpub, where Misti Norris, one of Dallas’ most creative and avant-garde new chefs, had accented a plush, cool tartare with puffed rice, plum, fennel pollen, sour honey and dill.

Either one might make you a believer in lamb.

The meat in both cases came from Sterling Lamb, a family-owned business based on Hodges Ranch near Sterling City, 250 miles west of Fort Worth. The Texas legislature has recognized Hodges Ranch as one among the state’s farms and ranches to reach the historic 100- year mark. Meanwhile, Clinton Hodges, 80-year-old patriarch and fifth-generation sheep rancher, is a case study in the challenges and rewards of breaking with the past and adopting new models. In a state where matters touching agriculture and livestock have deep implications and a raft of history, Hodges’ forward thinking positions him as part of the sheep industry’s emerging future, a future of niche markets.

If Hodges is now supplying Dallas chefs with boutique, all-natural, pasture-raised lamb, it’s because less than a decade ago, when he was well past 70, he made a bold move, transitioning from raising wool sheep, bred for fiber, to hair sheep, bred for meat.

On the Hodges’ ranch you’ll find not the fluffy creatures of bedtime reveries, but a flock of sheep with no more than a thin coat on their backs, more similar to the hide of a cow. These sheep reflect a changing industry.

In 2008, when Hodges’ pioneering move was well underway, the U.S. sheep and lamb industry was in a precarious place. Texas is a bellwether for understanding the vacillations of the national industry. Introduced with the first Spanish settlers in the late 1600s, sheep ranching grew in Texas until it reached a peak in the midnineteenth century, when American ranchers introduced increasing numbers of wool sheep breeds and New England presented a strong wool market. By the 1930s, Texas was the largest producer of sheep in the country, most of them wool sheep breeds. But starting in the 1940s, the industry began to decline.

Clinton Hodges, 80-year-old patriarch

and fifth-generation sheep rancher,

is a case study in the challenges and

rewards of breaking with the past

and adopting new models.

In 2008, the National Academy of Sciences published a report tracking this downward trend from a high in the 1940s (56 million head) to 2007 (6.2 million). The report cited multiple factors: competition from other meats and fibers; foreign wool subsidies; a strong U.S. dollar relative to currencies in Australia and New Zealand, the two other leading sheep and lamb producers, whose product was less costly; even American G.I.’s negative encounters with mutton while serving in Europe during WWII. By the 1990s, when subsidies established by the Wool Incentive Act were withdrawn, raising wool sheep, especially with the cost of shearing factored in, left miniscule profit margins. And yet, the committee also saw hope, notably in the rise of hair-sheep breeds and the emergence of new and niche markets.

They could have been talking about Hodges.

“We were in the Rambouillet sheep business,” Hodges says of the model that had sustained five generations. “My father and grandfather both raised wool-type sheep. All of my life, I was raised into it.” In the early ’90s, he was still exporting fiber all over the world. “But we were seeing a change in the wool industry here in the U.S. The numbers were going down and sheep shearers were getting hard to get. We decided it was time for a change.”

Hodges bought his first hair sheep in 1994.

“Nobody ever thought that hair sheep would take over the way they have,” he says, estimating that 85 percent of sheep in Texas are now hair sheep. Nor was it an easy decision. “We’d shown our Rambouillet [wool sheep]. We’d been successful with them. They’d really been good to us. But we could see that things were changing.”

So in ’94 and ’95, he started transitioning his flock, aiming to fill a need amongst customers seeking high-quality, hormone-free lamb. “I never envisioned us getting into specialty lamb meat,” says his granddaughter, Courtney Hodges, the DFW representative for Sterling Lamb (something she does in addition to her full-time job in Dallas). “I didn’t see that coming at all.”

Hair sheep are relative newcomers to U.S. ranches. Native to hot and often tropical climes, where woolly coats present disadvantages, hair sheep breeds are well suited to Texas. They are also more parasite- resistant, require no shearing, and their meat is free of the gaminess that results from the lanolin compounds that contribute to wool growth in wool sheep, according to Courtney. But few ranchers were raising them, and Hodges found himself learning a new set of breed characteristics and entering a new market. He worked closely with Texas Tech and Angelo State University, enlisted help, secured grants.

Meanwhile, Hodges remembers fellow ranchers’ at times overt hostility, based in part on concerns about hair-sheep hairs, caught in fences, infiltrating their flocks’ wool, Hodges says. (Inseparable mechanically, the hair doesn’t hold dye.) “There were a lot of people who really criticized us for what we were doing. Some of the old wool line people really gave me a hard time. You’d bring in a skin and they wouldn’t even touch it. But it didn’t bother me,” Hodges says. “It didn’t bother me at all.”

Courtney, who was a teenager at the time, remembers how little known hair sheep were. She and her siblings were used to showing the family’s sheep at stock shows. Many shows didn’t recognize hair sheep as a category. It was too new, she says. “When people do things for a really long time, it’s tradition.”

Courtney approaches the entire matter with the clear-eyed, contemporary perspective that comes from having a BA in agricultural economy and agricultural business. Initially, her thought was not necessarily to join the family business, but from her first years as an undergraduate at Texas A&M, her grandfather was asking, “So when are you going to finish college and come home and run [Sterling]?”

When she did join, the family operation was so small in its new, fledgling form that she shuttled deliveries in an ice chest in her car, squeezing in trips before and after work.

Courtney articulates the challenges of being small. One of the biggest, once Sterling had animals ready for slaughter, was finding a processor. “We’re not big enough to be attractive to a big one; too big for a mom and pop,” she says. They also needed a cadre of chefs who would work with them. One chef turned them down, saying the racks weren’t big enough for him to use. Hair sheep, by nature, are not as big as Rambouillet.

In many cases, generally, “What chefs want is a boutique business that can provide volume when they need it,” Courtney says. But the reality is that “there are only two French racks per animal; but there are 14 pounds of leg per animal.” She struggles at times to juggle requests. “Everybody wants shanks or sirloin.”

Opposite: Joyce and Clinton Hodges, 1953.

Opposite: Joyce and Clinton Hodges, 1953.

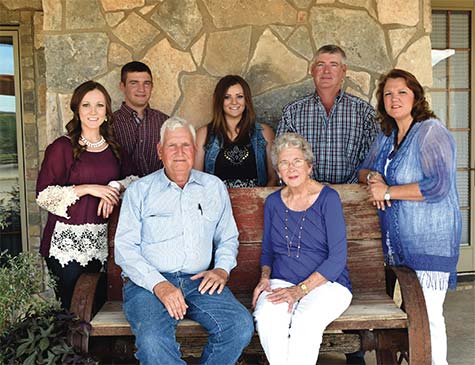

Above: The Hodges Family—(front) Clinton and Joyce;

(back) Courtney, Kade, Kalyn,Wesley, Karen.

Meanwhile, the idiosyncrasies of being a small business provide a chance to see a community that’s like a village.

Matt McCallister, chef-owner at the innovative, high-end, farm-totable restaurant FT33, was Sterling’s first Dallas customer. Wood from the Hodges’ torn-down barn panels the restaurant’s dining room, a product of a visit to the ranch and a visual reminder of Mc- Callister’s ethos. He is sensitive to Sterling’s position; their size and artisan approach is part of why he wants to support them.

“Small ranches don’t process enough animal for me to be, like, I just want this one cut,” McCallister says. Working with lamb sparks his creativity. His charcuterie board features pickled lamb’s tongue prepared pastrami-style. A spring entrée featured a duo of slow-braised shank and merguez-spiced lamb sausage, served with mint and coriander salsa verde.

Omar Flores, chef and owner of Casa Rubia in Trinity Groves, has served lamb shoulder at his restaurant, and a lamb shank dish bursting with Moroccan-inspired flavors. “Lamb holds up to those bold flavors,” he says. “I love beef. I mean, this is Texas. But beef is kind of overplayed. To me, there’s just so many more exciting cuts of protein out there.”

Flores was drawn to Sterling’s quality and their story. “[Courtney] kind of sold me on it right away, told me about the practices and the farm. It’s always nicer to use local when you can.” And like McCallister, Flores is adaptable, open to switching to fore shanks when Sterling ran low on hind shanks.

Ultimately, Courtney says she would love to achieve a fully coordinated supply chain. “The perfect [business] model is one such that you have a destination for all product types,” she says.

That both McCallister and Flores say their lamb items sell well flies in the face of “received” notions about consumers’ attitudes towards lamb—that it is gamey, pungent. Still, a large part of Courtney’s job is raising awareness, even among chefs.

Customers can order meat directly through Sterling Lamb’s website. The order form lists whole carcasses, shanks, loin or spiral-cut legs, but also bacon and salami links, priced individually and shipped via next-day delivery.

“I see it as a business that my grandkids

can carry on and make a living of it. . . .

The traditional lamb business they

cannot, but with this I think they can.”

— Clinton Hodges

photo by Kalyn Hodges

photo by Kalyn Hodges

“My experience is that we’ve converted a lot of people to liking lamb,” she says. According to her, the main barrier is often a lack of cooking confidence. She and her sister Kalyn have contributed recipes to the website’s recipe blog, suggesting everything from barbecued lamb meatballs and lamb tacos to a considerably more daunting rotisserie leg of lamb.

Last year was a banner year for Sterling, the year Courtney says she saw things shift. “I’ve been able to watch and track our growth. Early 2014 was when I started feeling really good,” she says.

She has had to make sacrifices to continue the family business, for example deciding not to pursue a masters under a professor she greatly admires who recently retired from Texas A&M. She would have been his last research assistant. “It was hard; it was very hard.

But I can’t say I have any regrets,” she says. The reason, quite simply: “Granddad”—and his vision of something sustainable, a legacy to pass on.

“He didn’t see as much of a future in the standard ranching model,” says Courtney. “Here, [in hair sheep] he saw something he wanted to pass to us.”

“I see it as a business that my grandkids can carry on and make a living of it,” Hodges says. “The traditional lamb business they cannot, but with this I think they can.”

It means a lot to Courtney that at this stage in his life, her grandfather “gets to see it work.”

EVE HILL-AGNUS teaches English and journalism and is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She earned degrees in English and Education from Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Dallas Morning News, D Magazine, and the journal Food, Culture & Society. She remains a contributing Food & Wine columnist for the Los Altos Town Crier, the Bay-Area newspaper where she stumbled into journalism by writing food articles during grad school. Her French-American background and childhood spent in France fuel her enduring love for French food and its history. She is also obsessed with goats and cheese.

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/