A Local Look at the Search for Talent to Incubate

“This contest kicked off over 10 years ago in an effort to highlight what we were already doing, which was supporting local businesses,” says Jody Hall, who launched the H-E-B Quest for Texas Best. When Florence Butt opened her tiny grocery store in Kerrville in 1905, the predecessor of all H-E-Bs, Hall points out, “she was buying local products.”

Hall has worked for H-E-B for 33 years and led sourcing for 22. The Quest program was inaugurated in an effort to use the grocery store chain’s resources to help champion local entrepreneurs.

“The first year, it was more of a recipe contest,” Halls says. “They had an idea, but they didn’t have a finished product.” Contestants brought their goods in Tupperware containers and Crock pots. Now, as farmers markets and cottage businesses—and the social media appetite for polished presentation—have grown, they often come with retail-ready packaging.

The program helps contestants in any way it can, connecting them with the GoTexan program, Texas A&M, and others that can help co-pack or co-manufacture or aid in small business management. It’s not just the cash prizes—$10,000 for each finalist this year, and $25,000 for the Grand Prize. But “Where do you need help?” Hall asks. “Quality assurance? Packaging and design? Keeping your books?” They try to reach all their finalists.

Nor is it just queso and kolaches. Diversity has increased over the years, with more women-owned and veteran-owned businesses, and finalists whose products harken to their roots in Vietnam, Colombia, France, the Dominican Republic of Congo, or Tunisia. Each tells the story of a diverse state.

TEXAS BEST SPOTLIGHTS

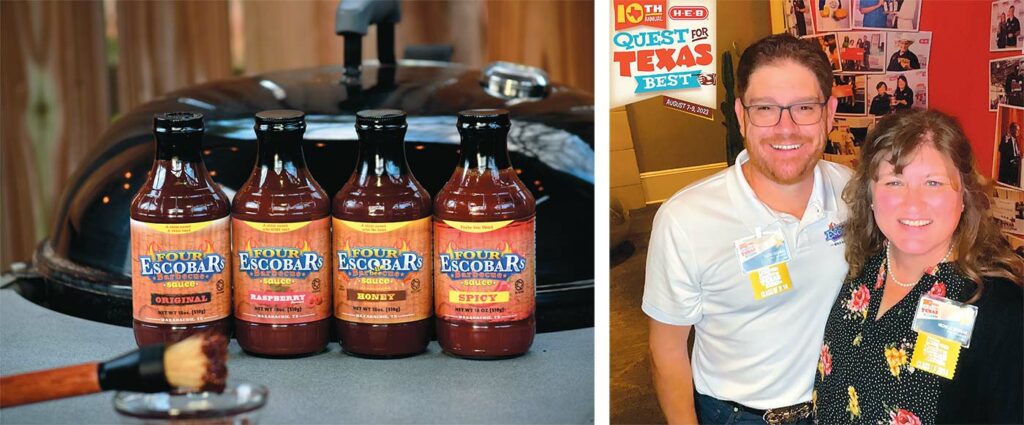

FOUR ESCOBARS BARBECUE SAUCE

A sweet and spicy story of success.

Theirs is hardly an unlikely story for a barbecue sauce business: It all started with the barbecue competition circuit. Cletis Escobar, born and raised in Waxahachie, had long enjoyed the siren of smoke and ember when he began crafting his own sauce.

“Hey, if you make it next time, I’d like to have some!” he remembers friends and neighbors saying. A mark of confidence, certainly. Finally, when a neighbor who owned a grocery store advised him to put his creation in a bottle, Cletis took eight months to hone the flavor of what would become his “original” sauce—now one of four.

When he learned of H-E-B’s Quest for Texas Best competition, he and his wife Michelle submitted their essay just minutes before the deadline, closed their laptop, and went to bed. During the nine years since they placed as finalists in that year’s Quest (2014), they have gone from zero commercial representation to presence in 240 stores across the state.

Of the four flavors—original, raspberry, honey, and spicy—the raspberry derives from Cletis’s fondness for grilling chicken. A self-described “white-meat guy,” he won a grand championship based on his way with what can be considered an afterthought in the fiercely competitive barbecue world. The raspberry sauce’s smoky chipotle flavor, he found, was his secret weapon.

Cletis and Michelle’s youngest son, now 19, designed the bee on the honey-hinting sauce’s label, and the recipe features local Burleson’s honey from Waxahachie: one of Cletis’s high-school classmates is behind the sweet operation.

All four Escobars—Cletis, Michelle, and their two sons—have backed the business in their own ways. A fan of thicker, coating barbecue sauce, Cletis always wanted an elixir that “hit every single taste bud, all around your mouth,” he says—a little vinegar, a little sweetness, a little heat. And that was, ideally, irresistible. Sometimes, he admits, “I’ll just stick a potato chip in it. That’s what we’re looking for.”

ARMAGH CREAMERY

From Ireland to Northern California to Texas

They named it Armagh: a moniker taken from the county in Northern Ireland from which Ryan McDowell’s family hails. But Armagh Creamery—which won 3rd Prize in this year’s Quest for Texas Best, and which Ryan co-owns with his wife Katie, father Mike, and stepmother Linda—resides in Dublin, Texas, not on that fair green isle.

Ryan and Katie were the fifth generation McDowell dairy farmers to raise cows just outside the stunning, picturesque Bodega Bay in what is known as the Petaluma Dairy Belt in Northern California. Their organic milk was sold to a cooperative.

Meanwhile, 13 years ago, Mike relocated to Dublin, Texas to help others launch an organic dairy, and, after some coaxing, convinced his son and daughter-in-law to consider an opportunity to distinguish themselves; in 2019, they, too, moved to Dublin.

“We wanted to be able to make our own product on the farm,” Ryan says, crafting a legacy rather than selling to a cooperative.

They came into a landscape with little organic dairy and few soft-ripened cheeses. “There’s a lot of really great cheddars and hard cheeses,” Katie says, but they could see a niche. From the 80 or so Jersey cows (“We really love Jerseys because they have such great butter fat,” Katie says) and Holsteins (greater milk volume) on their 700 acres (as compared to 300 acres in California), they craft a Brie-style cheese in addition to their incubated-in-the-cup, European-style yogurt, and also sell raw milk. As a grade A product, the yogurt they wanted to make has a high level of regulation, requiring expensive pasteurizing equipment for a small business. But they dreamed of the possibilities, and central Texas gave them access to all the major cities.

Their cows graze in the late fall and spring (120 days a year), and the McDowells supplement their diet with alfalfa and homegrown sillage—winter wheat in the cold months and native Coastal Bermuda grass in the summer. “That’s one of the advantages of our farmstead in Texas is that we’re able to grow our own [organic] feed,” Katie says.

They use only real ingredients in their yogurts: plain, vanilla-honey, maple, blueberry, and strawberry. The goal is that they “taste as close to homemade as possible,” Katie says. In many ways, they are pioneers, the first in the family to foray into crafting artisan organic dairy products from their milk. The first pioneers were the ones who came from Ireland, Ryan reminds me. It’s true. Fair enough.

For information about submissions (in April 2024), visit www.heb.com/static-page/quest. Check Edible Dallas Fort Worth’s social media for updates on the application and awards announcement.

EVE HILL-AGNUS teaches English and journalism and is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She earned degrees in English and Education from Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Dallas Morning News, D Magazine, and the journal Food, Culture & Society. She remains a contributing Food & Wine columnist for the Los Altos Town Crier, the Bay-Area newspaper where she stumbled into journalism by writing food articles during grad school. Her French-American background and childhood spent in France fuel her enduring love for French food and its history. She is also obsessed with goats and cheese.

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/

- Eve Hill-Agnushttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/ehillagnus/